Analysis - Explaining China's Climate Policy

By Kasper Sulkjær Andersen

This article is a part of a master's thesis from 2013.

5.0 ANALYSIS – EXPLAINING CHINA’S CLIMATE POLICY

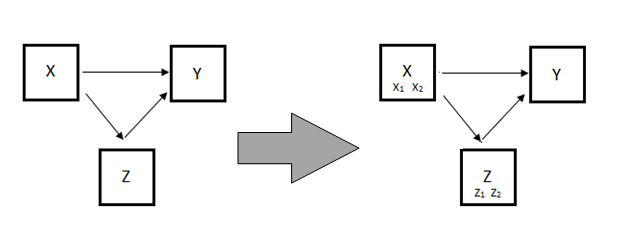

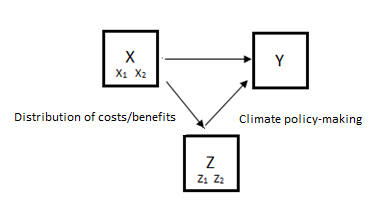

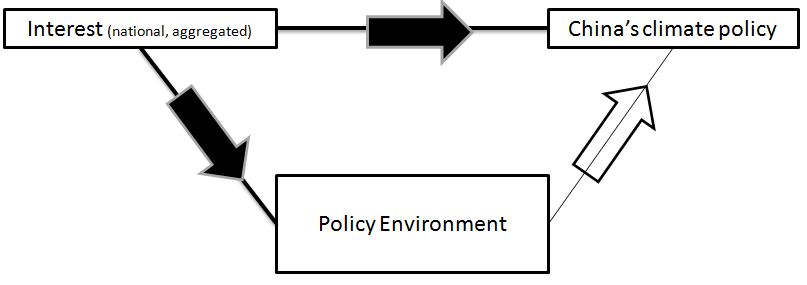

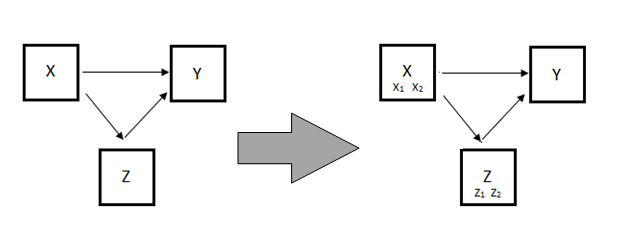

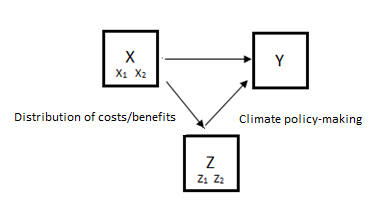

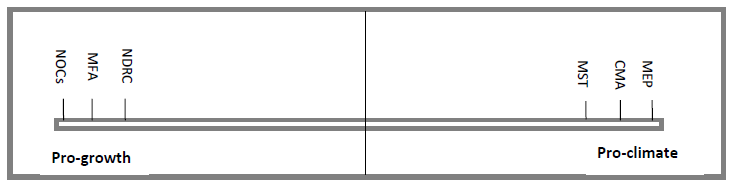

The present analysis will be structured according to the analytical model (see Figure 2.4) presented in Section 2.4. The analysis is guided by the theoretically derived causal relationships captured by Model A and B. The causation suggested here, comprises both a direct as well an indirect causal relationship (see Figure 5.0).

Figure 5.092

As has been elucidated in more detail elsewhere93, the causation suggested in the present dissertation features a direct causal relationship between China’s national aggregated interest (dependent variable (X)) in terms of climate change and the level of proaction in China’s climate policy. China’s national interest, in turn, depends on the ratio between the costs associated with its climate vulnerability (X1) and its abatement costs (X2) associated with reducing GHG emissions. It follows that only in the situation where the costs of climate vulnerability outweigh abatement costs will China’s national aggregated interest cause a proactive shift in climate policy and vice versa. This direct causation is both mediated and complemented by another and indirect causal relationship (from X to Z; Z to Y) which has ramifications for the resultant climate policy. Firstly, it is posited that China’s national interest (X) exerts an influence on the policy environment in which China’s climate policy is embedded. Namely, I argue that the contents of China’s national interest in regards to climate change will, at least partially, impact the interests (Z1) of China’s climate policy actors thus affecting the behaviour of these in the subsequent policy-making process. Secondly, turning to the causation between Z and Y it is posited that the likelihood of formulating a proactive climate policy depends on the presence of a conducive94 policy environment (Z) which, in turn, depends on the interests (Z1) embedded within the Chinese political system as well as the relative power (Z2) between the involved political actors. It follows that when the interests of the most powerful political actors within the Chinese political system are aligned with the national aggregated interest then the likelihood of formulating policies in accordance with the national interest increases and vice versa. It is further assumed that the interests of domestic political actors are simultaneously shaped by national interest and organisational interests. However, organisational interests weigh more heavily on the decisions of political actors (Conrad, 2010).

Based on Figure 5.0 the aim of the present analysis is then to ascertain either the existence or the absence of the suggested causal relationships. In doing so, the analysis will progress in interrelated stages. The first stage (5.1) will analyse the nature of China’s national aggregated interest in terms of climate change based on the unitary actor model (Model A). Model A posits that the contents of China’s national interest will determine its climate policy. The second stage (5.2) will, building on China’s national interest, ascertain either the presence or absence of a conducive policy environment (Z) within the Chinese political system. This stage will be based on the domestic politics model (Model B) which posits that China’s climate policy environment will either constrain or amplify the contents of the national interest.

5.1 DIRECT CAUSATION: GAUGING CHINA’S AGGREGATED NATIONAL INTEREST

The present analytical section consists of three main analytical elements: The first element will seek to determine China’s level of climate vulnerability and the associated economic costs of this vulnerability. The second analytical element will seek to determine China’s level of abatement costs associated with reducing GHG emissions. The third element building on the findings of the two former elements will facilitate a cost-benefit analysis which, in turn, will serve as an explanation of China’s climate policy.

5.1.1 X1: CHINA’S LEVEL OF CLIMATE VULNERABILITY

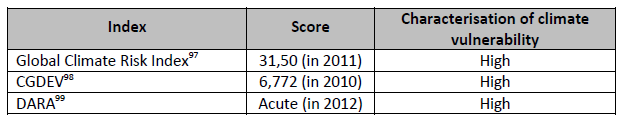

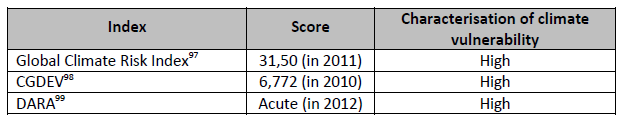

Climate change experts located both ‘inside’95 and ‘outside’96 of China estimate that the costs of climate change in China are significant – at present as well as in the future. From the IPCC’s (2007) fourth assessment report published in 2007 we know that Asia is likely (with high confidence) to be particularly affected by changes in weather patterns and sea-level rise due to increased surface air temperatures as a direct result of climate change (IPCC, 2007:471-506). Particularly, the occurrence and intensity of extreme weather events such as droughts, floods and cyclones is likely to be exacerbated. These events will, in turn, affect the availability of water, arable land, as well as impact human health. This picture is congruent with the high vulnerability ranking of China according to authoritative vulnerability indices (see Figure 5.1):

Figure 5.1

In a report prepared for the 2006 Stern Review, prominent Chinese climate scientists assert that “(...) China is most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change on water resources, agriculture, ecosystems and coastal zones, and the direct impacts of natural disasters on human life and infrastructure” (Lin et. al., 2006:2). Not all of these impacts, however, can be characterised as direct impacts but rather as a combination of direct and indirect (associated) impacts100. According to Lin et. al. (2006) the most tangible expression of the direct impact of climate vulnerability in China is the combination of sea-level rise101 and the occurrence of extreme weather events (droughts/floods102, cyclones103). Taken together, these direct impact-components represent the direct costs of climate change in China.

The associated impact of climate change, on the other hand, flows from the former direct impact component and captures the second-order effects of changed climatic conditions. In China, agricultural production104 is the indirect-impact component deemed most susceptible to climate change (IPCC, 2007:472) and it is the costs incurred by China as a result of reduced agricultural production that represent the indirect costs of climate change.

5.1.1.1 THE DIRECT COSTS OF CHINA’S CLIMATE VULNERABILITY

THE COSTS OF EXTREME WEATHER EVENTS

This part of the analysis relies on data available from the International Disaster Database (EM-DAT), which, apart from logging the occurrence of extreme weather events, provides estimates of damage costs of these events both in terms of direct and short-term associated costs.

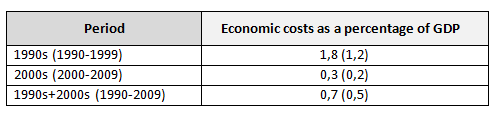

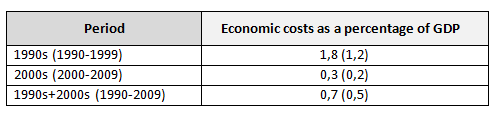

Based on my own calculations using data from EM-DAT I find that the economic costs of extreme weather events in China in the period from 1990 to 2009105 have accrued in the following way:

Figure 5.2106

Figure 5.2 shows that the economic costs of extreme weather in China amounted to an average of 1,8 percent of annual GDP in the 1990s and 0,3 percent of annual GDP throughout the 2000s. Overall, the total damage costs in the period was equal to a 0,7 percent loss of annual GDP. The bracketed numbers in Figure 5.2 reflect that only a given proportion of the total amount of extreme weather events in China are caused directly by climate change. In order to adjust the numbers for this inaccuracy the results are multiplied by a factor 0,65 as Lin et. al. (2006:14) estimate that roughly 65 percent of the costs associated with extreme weather in China is a direct result of climate change.

My findings are congruent with the calculations undertaken by the German-based NGO GermanWatch which publishes annual cost estimates based on their climate risk index107. This index ranks the countries of the world according to the extent and cost of their individual vulnerability to climate change. According to the latest report from 2013108 China ranks as number 2 (in the period from 1992-2011) in terms of total damage costs associated with climate change, which translates into 0,54 percent loss of GDP across the 20 year period.

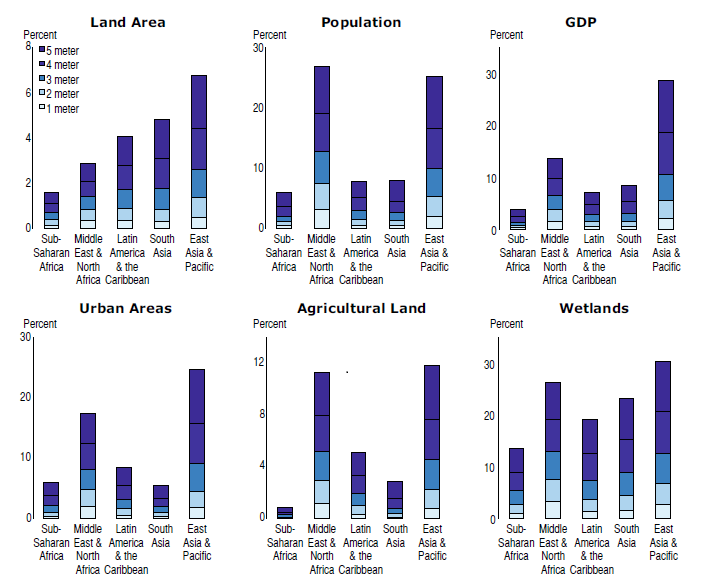

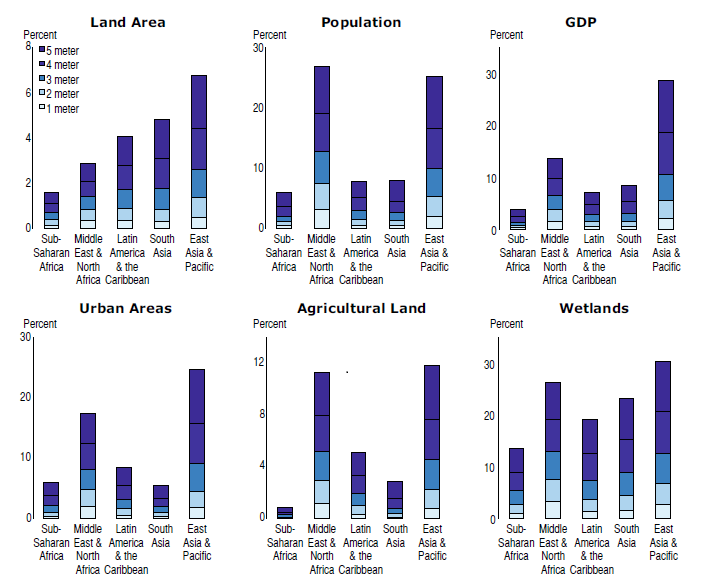

THE COSTS OF SEA-LEVEL RISE

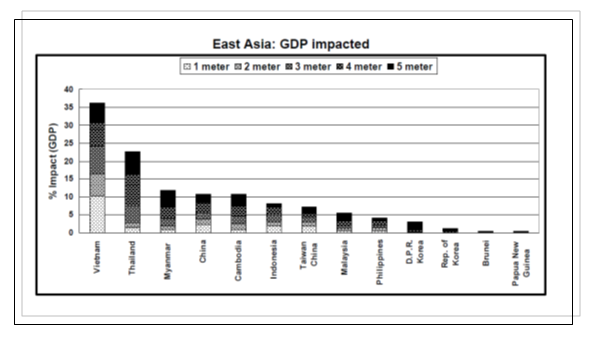

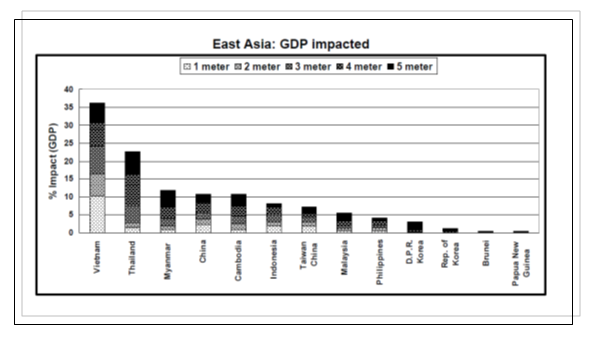

The calculations above reflect the actual damages of China’s climate vulnerability within the past twenty years. The same retrospective calculation is not possible as sea-levels are only incrementally changing. According to the IPCC (2007:484) the current global rate of sea-level rise amounts to 3 mm per year on average which makes the prospective costs of sea-level very long-term. The global trend conceals the fact, however, that the rate of sea-level rise varies significantly across the globe. In Asia the rate of sea-level rise is likely to deviate from the mean global trend by exhibiting a higher than average rise in the rate of sea-level rise (IPCC, 2007). The projected rate of change suggested by the IPCC (2007) is predicated primarily on estimates of thermal expansion due to increasing temperatures. However, new research shows that the rate of deglaciation in Greenland and Antarctica is higher than expected which has the potential to substantially speed up the rate of sea-level rise. According to Dasgupta et. al. (2007; 2009) an increase of 1 m by the turn of the present century is not an unrealistic projection which lies significantly higher than the projections of the IPCC (2007) as these are based predominantly on thermal expansion. Based on 6 indicators, Dasgrupta et. al. (2007) compute the impact of a 1-5 meter sea-level across those of the world’s developing countries with coastal zones (see Figure 5.3). Given the net present value of these computations the findings of Dasgupta et. al. (2007; 2009) should be interpreted as a snapshot of the impact of sea-level rise if this was to occur at the present point in time109.

The findings of Dasgupta et.al. (2007; 2009) (see Figure 5.3) show that out of the 5 included regions, East Asia and the Pacific is the region most severely impacted by rising sea-levels.

Figure 5.3110

Looking at China in more detail in terms of the impact on GDP (see Figure 5.4) China is the fourth most affected country within the East Asian region.

Figure 5.4111

Translated into numerical terms the expected damage costs of GDP, according to Dasgupta et. al. (2007; 2009), as a result of a 1 m increase is equal to 2,40 percent. In the case of a 3 meter increase in sea-level the corresponding damage costs equal 5,59 percent of GDP112. Both scenarios are possible; however, a conservative estimate would assert that a 1m increase is the more likely of the two. By any standard a 2,40 percent loss of GDP due solely to rising sea-levels is substantial which coupled with the direct costs of China’s climate vulnerability in terms of extreme weather events makes the combined effect of climate change an issue of economic gravity.

5.1.1.2. THE INDIRECT ECONOMIC COSTS OF CHINA’S CLIMATE VULNERABILITY

As noted above, the direct impact is only half of the equation given that the associated costs of climate vulnerability are likely to be as high as the costs of the direct impact of changing climatic conditions. In China, agriculture is, by experts (IPCC, 2007), deemed the most susceptible sector to changing climatic conditions, which warrants this sector by treated as the main exponent of the indirect impact of climate change.

AGRICULTURE

Gauging the economic costs incurred by China as a consequence of its climate vulnerability relies on estimates from Cline (2007)113. Cline (2007) has been chosen as the primary reference as his work incorporates the findings of the few other agricultural impact studies currently published in terms of global climate change. In this sense, Cline’s (2007) work can be understood as representing the middle ground in terms of the likely impact of climate change on agriculture. According to Cline (2007) changes in temperature and precipitation patterns are the two most important ways in which agriculture can potentially be impacted by climate change. A favourable ratio between increased temperatures and precipitation can potentially heighten the conditions for agricultural production and increase yields. Ideally, average temperatures should lie somewhere around an optimal level of 14,2°C in order for agriculture to thrive. Temperatures significantly below or above will have adverse effects on agriculture discounting differences in patterns of precipitation. Building on the intermediate A2 climate scenario (a 3°C increase in average temperature), suggested by the IPCC (2007), as the most plausible GHG emission scenario Cline (2007) calculates the likely change in agricultural capacity i.e. the change in agricultural output for the final three decades of this century (2070-2099). In terms of China, Cline’s (2007) projections (without the effect of carbon fertilisation114) indicate that all Chinese regions, apart from the Tibetan plateau, stand to lose from climate change. The magnitude of these losses differs markedly across regions with small losses to the north and central parts of China and significantly higher losses in the southern regions. In aggregated terms, China’s agricultural production is likely to be reduced by 7,1 percent (which equals a -15340 change in million 2003 USD) compared to the baseline scenario of no changes in temperature and precipitation. In terms of GDP, which has been left out by Cline (2007), my own calculations suggest that the total loss in agricultural production translates into roughly 1 percent of annual GDP115.

To summarise, the two sub-sections above analysing the total economic costs associated with China’s climate vulnerability find that the costs of changing climatic conditions in China are likely to be substantial. In terms of the direct impact of climate vulnerability China has incurred economic costs equal to 0,5 percent of GDP from extreme weather events in the period 1990-2009 and is projected to incur 2,4 percent of GDP as a result of a 1 m sea-level rise. Coupling these estimates with the projected costs of a reduced agricultural output adds a cost estimate of 0.9 percent of GDP. Although at first glance the magnitude of the actual and projected climate costs may seem modest or even insignificant it is important to emphasise that forfeiting nearly 4 percent of total annual GDP as a consequence of climate change is a substantial wastage of productive resources by most standards116.

5.1.2 X2: CHINA’S ABATEMENT COSTS117

Turning to the second variable in Model A, abatement costs are more straightforward to calculate than the costs of climate vulnerability since abatement costs can be expressed in concise cost functions based on country characteristics. Abatement costs are generally expressed in relative terms as a percentage of GDP and measure the costs of reducing GHG emissions given a particular reduction scenario. In other words, abatement costs can be understood as imposing an opportunity cost on an economy i.e. costs that could have been saved or invested elsewhere depending on preferences. In that sense, I would argue that abatement costs can simultaneously be perceived as representing both the costsaction or the reverse benefitsinaction, which will be elaborated below.

Depending on the depth of emission cuts needed to achieve a given target abatement costs can be computed. The extent of the costs depends on the shape of the cost function which, in turn, depends on the parameter (α) and the exponent (β) applied in the cost function. These are again contingent on specific country characteristics. It follows that the deeper the necessary emissions cuts the more expensive abatement will be. The analysis below is based on the RICE-model developed by Nordhaus (2008) as this model represents the middle ground in terms of abatements costs118.

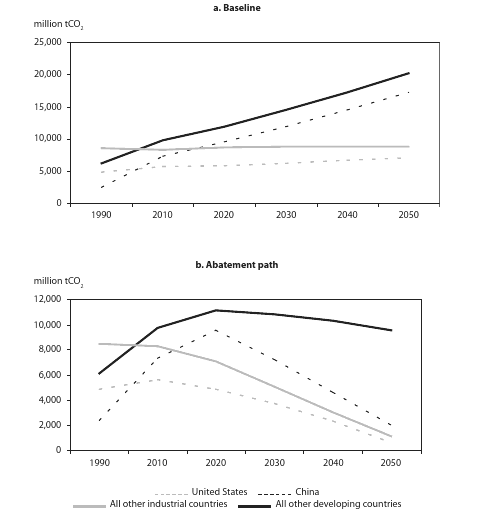

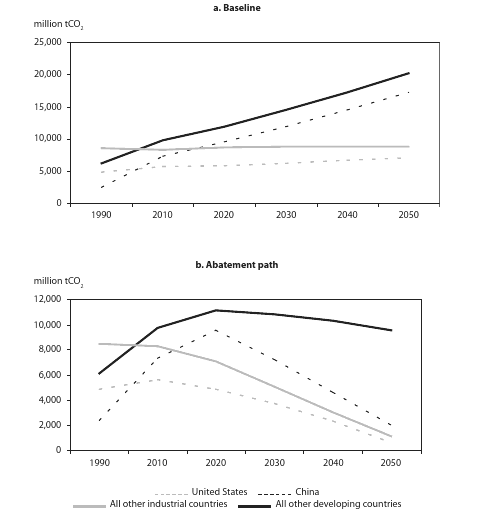

In order to compute China’s abatement costs I will rely on the emission reduction scenario proposed by Cline (2011). Based on the difference between the current trajectory of baseline emissions and the trajectory pledged to by countries during the COP 15 in Copenhagen, Cline (2011) finds that in order to stay within the 2°C temperature bracket (450 ppm carbon dioxide) proposed by the Copenhagen Accord119 this would entail a global emission reduction of approximately 9 percent (3,2 GtCO2) by 2020 assuming that all countries actually manage to fulfil their respective emission obligations. After 2020 Cline assumes that countries will start to converge around identical per capita emissions by 2050. In order to stay within the aforementioned temperature bracket the world’s countries will need to converge around a 1,43 tCO2 in order to facilitate an emission “(...)level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system (…)” (Copenhagen Accord, 2009:5). In order to achieve this target the countries of the world need to reduce emission by 75 percent on average; for the developed world this translates into a reduction amounting to 89 percent and for the developing world into a reduction of 69 percent. In economic terms according to the RICE model this reduction scenario would cost 1,15 percent of global GDP for the world as a whole and 1,55 percent of GDP and 0,98 percent of GDP for the developed and developing world respectively.

In order for China to achieve its Copenhagen Accord pledges of reducing carbon intensity by 40-45 percent of 2005 levels as well as increase the non-fossil by 15 percent in the overall energy mix, Cline (2011) estimates that China would not incur any abatement costs in the short run until 2020 as the increases in energy efficiency offset the need to reduce emissions. However, over the longer run China has to significantly reduce its overall emissions in order to converge around the target of 1,43 tCO2 per capita (see Figure 5.5). Figure 5.5 illustrates that given China’s (2011) baseline scenario where emissions are likely to follow a steep upward sloping trajectory the divergence between the baseline and the convergence scenario suggested by Cline (2011) is likely to be significant. This translates into a substantial drop in emissions after 2020. According to estimates by Cline (2011), China needs to cut emissions by 88 percent of 2020 levels by 2050 which translates into an abatement cost of 2,13 percent of GDP (or 1282,9 billions 2005 ppp US$ in total costs). China’s total abatements costs can only be characterised as substantial seeing that they amount to more than twice as much as the average for developing countries and almost 1½ times that of the average of the developed world in Cline’s (2011) reduction scenario. Looking at Figure 5.5 and the slope of the trend line in b clearly shows that the comparable decline of China in terms of emissions is much steeper than that of the rest of the developing world and the developed world. In comparison to the US, China’s reduction after 2020 is much more abrupt than that of the US which is smoother and more linear.

Figure 5.5120

Looking past the numbers, I would contend, however, that Cline’s (2011) calculations above represent China’s abatement costs under ideal conditions. From the perspective of politic science and certainly given the track record of climate change negotiations so far I find it highly unlikely that the emission reduction scenario proposed by Cline (2011) would actually unfold in the coming decades. Particularly, issues over the equal distribution of emission rights and the convergence towards a common per capita emission target are two cases in point that up until now have remained unresolved and to a large extent kept countries from accepting binding commitments in the future. Most likely, future efforts on climate change will reflect past efforts and as a result are likely to be less ambitious than those proposed by Cline (2011). This is particularly true for China given its lead position in the G77 coalition’s call for the right to development. The point being that efforts falling short of Cline’s (2011) scenario also result in smaller abatement costs. Therefore, Cline’s (2011) calculations can be said to represent the highest amount of abatement costs that China will incur121. How much smaller China’s actual future abatement costs will be is impossible to accurately predict but judging from past examples of China’s climate negotiating strategy I find it likely that China will emulate the efforts made by other developing countries.

5.1.3 COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS – EXPLAINING THE SHIFT IN CHINA’S CLIMATE POLICY

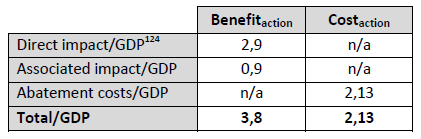

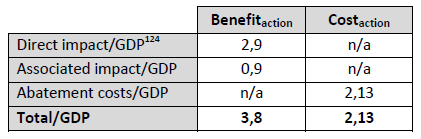

Now that the magnitude of China’s climate vulnerability and its abatement costs have been determined Model A can be utilised. Model A posits that if the condition benefitaction > costaction122 is met in terms of climate change, then China will be inclined to pursue a proactive climate change policy.

The simplest way to proceed analytically is to aggregate the findings of the analysis. However, complications arise as some of the costs are future or projected costs whereas others are actual or real costs making a summation problematic without further considerations. To my mind, the least contentious way forward is by assuming that from the perspective of China there is no qualitative difference between projected damage costs and current damage costs. At first glance, this assumption may seem farfetched, however, taking into consideration that whichever set of climate actions China implements today will determine the extent of future damage costs related to climate change it becomes clear that the distinction between current and future costs is less obvious. Hence, from a Chinese perspective the policy solution to reducing climate costs is the same today as it will be in the long run, thus blurring the distinction between the two temporal types of costs.

Another complication of methodological relevance in the present context is that predicting the exact magnitude of economic damage costs associated with climate change is contentious. In order to mitigate this methodological concern I have consciously selected the components of China’s climate vulnerability which have, by climate experts, been deemed the most tangible and relevant effects of changed climatic conditions in China. Also, in terms of the associated costs I have only included the agricultural component since assessing the exact magnitude of other associated costs such as the wider disruption to the economic system and trade eludes efforts of quantification. Furthermore, the damage cost estimations are all, when given the option, conservative estimates as I have systematically chosen the lowest damage estimations possible. This, in combination with higher-than-average abatement cost estimates facilitates the harshest test environment for the utilised theory, thus avoiding a biased analysis. Despite these efforts some modicum of inaccuracy has to be tolerated.

In the cost-benefit analysis below, the term benefitaction is assumed to be the cumulative value of the projected costs of China’s climate vulnerability. This assumption flows from the notion that China, by way of addressing climate change, benefits from avoiding the costs associated with climate change inaction. In this sense benefitaction is the inversion of the term costinaction since failing to adequately address climate change will be costly; avoiding these costs benefits China economically.

The term costaction is assumed to equate China’s abatement costs since the economic cost of mitigating climate change can be perceived as an opportunity cost imposed on the Chinese economy. As before, the term has a dual meaning as costaction is the inverted expression of benefitinaction since the costs involved in mitigating climate change could otherwise have been saved or invested elsewhere if action on climate was deemed unnecessary.

The size of either term can be found in Figure 5.6 below.

Figure 5.6123

5.1.3.1 INTERPRETING THE COST-BENEFIT RATIO

The behavioural implications of the cost-benefit ratio summarised in Figure 5.6 would suggest that it is in China’s national aggregated interest to act proactively on climate change. Given the tenets of the unitary actor model (Model A) I would expect China to maximise its national utility by addressing climate change through the formulation of remedial policies i.e. the best remedy in order to gain from the current situation would be for China to increase its level of climate policy ambition. According to my aggregations China stands to gain (or more accurately save) 1,7 percent of annual GDP by taking a proactive policy stance on climate change which is a substantial saving for a developing country. Although there are no fully comparable benchmarks a sense of the magnitude of the saving gained from taking a proactive policy stance can be achieved by asserting that this saving equals roughly a sixth of China’s current growth rate125. Being a developing country governed by a political setup where economic performance is paramount to political legitimacy wasting a sixth of annual economic resources on climate change alone is politically untenable and certainly suboptimal from an economic perspective. A rapid response to climate change would both boost economic growth and speed up the current Chinese growth trajectory.

Likely to further impact the cost-benefit ratio underlying China’s national interest is its ongoing environmental crisis126. As has pointed out by Economy (2010) China is currently confronted by high levels of land degradation, water and air pollution as a direct result of China’s rapid industrialisation process. The environmental circumstances are now so dire that Economy (2010) alongside other experts (Economy and Lieberthal, 2007; World Bank, 2007; Delman & Odgaard, 2011) estimate that the costs associated with China’s ongoing environmental crisis could amount to as much as 8-14 percent of annual GDP. China’s climate policy response is likely to be affected by these cost considerations since the cause and, hence the solution to both problems, share a considerable overlap. The combined costs of both problems total roughly 14 percent of annual GDP127 which is more than enough to offset China’s high economic growth rate. For this reason, I would expect China’s environmental crisis to amplify the resultant response to climate change.

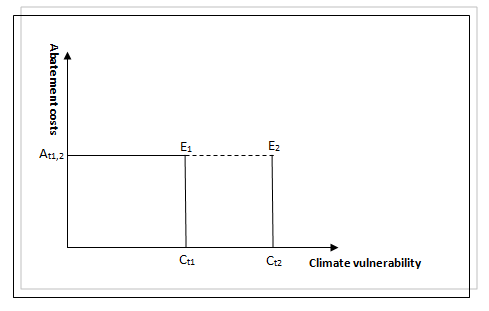

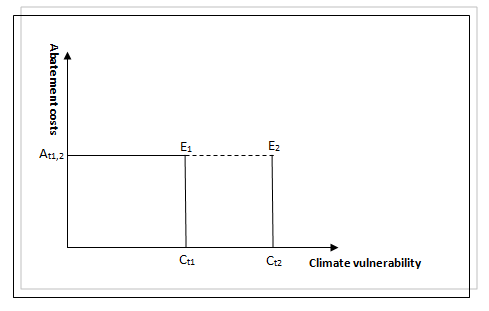

Thus, looking at China’s climate policy it seems fully congruent with the predictions of the theoretical framework captured by the unitary actor model. According to this framework, the recent shift in China’s national climate policy thus reflects increased Chinese awareness of the adverse climatic conditions currently facing China and the shift in policy can be conceived as China’s attempt to maximise national utility. However, assuming full rationality, as the unitary actor model does, one would actually expect China’s climate policy to exhibit an even higher level of climate policy proaction than what the current climate policy exhibits128. Borrowing from economic terminology, China would exhibit the highest level of rationality and utility-maximisation by exhausting its potential for climate proaction because only in this instance is full equilibrium restored (equivalent to position E2 in Figure 5.7)129 and climate mitigation at its peak. Nonetheless, China has yet to exhaust its potential for climate policy proaction130 and therefore currently finds itself somewhere on the punctured line between equilibrium-points E1 and E2. For this reason, the theoretical framework can expectedly only explain some of the variance in the dependent variable Y.

Figure 5.7

5.1.3.2 PREDICTING CHINA’S CLIMATE BEHAVIOUR IN THE LONG RUN

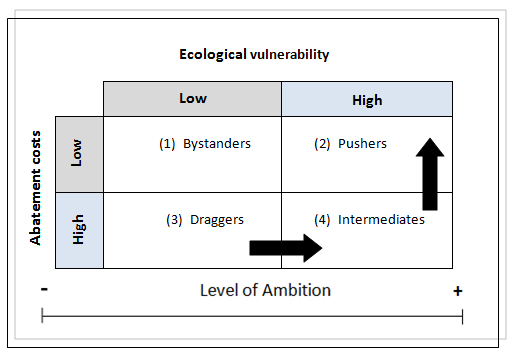

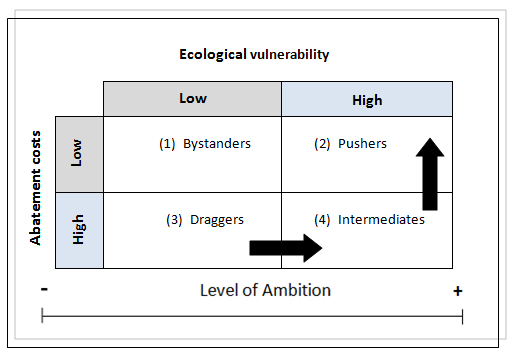

The cost-benefit ratio above only warrants an explanation of China’s behaviour in the short run based on China’s immediate national interest. Within this time frame abatement costs are assumed to be fixed. However, my adaptation of Sprinz & Vaahtoranta’s (1994) original model131 facilitates the prediction of China’s policy behaviour in the long run (see Figure 5.8).

Figure 5.8

The movement from position (3) to (4) represents China’s immediate national interest as highlighted by the cost-benefit ratio above. According to Model A, China’s position as a ‘dragger’ country ought to be gradually changing towards exhibiting behavioural tendencies more in line with that of an ‘intermediate’ country. Only climate vulnerability has increased in the relatively short period under consideration here whereas abatement costs have remained constant132. In the long run, however, the factors determining the level of abatement costs will be variable. As Sprinz & Vaahrotanta’s (1994) framework is designed to facilitate cross-country comparisons, China’s general level of abatement costs needs to be determined in relation to the abatement costs of other countries. Although Cline’s (2011) calculations could be used as a possible benchmark, the scenario, however, on which his calculations are predicated envisions a highly ambitious and concerted global policy effort to climate change which is unlikely to unfold making this scenario less apt at determining China’s ‘real’ abatement cost133. More than likely, China’s abatement efforts will fall short of the scenario proposed by Cline (2011) and hence its actual abatement costs will be smaller. A more realistic policy scenario would be one in which China manages to reduce some of its carbon intensity but not to the full extent of the proposed target of reducing carbon intensity by 40-45 percent (2005 level) by 2020. Stern et. al (2011) proposes a scenario where China reaches 2/3 of its carbon intensity targets. Based on econometric analysis and the EMF-22 abatement cost curve Stern et. al. (2011) find that China has the lowest abatement costs in terms of both marginal and total costs across the included countries (which comprise both developing and developed countries). This gives a clear indication that China under the circumstances of a more realistic reduction scenario will have relatively low abatement costs. According to Model A this implies that in the long run we would expect China to exhibit behavioural tendencies similar to those of a ‘pusher’ country (i.e. a move from position (4) to (2)). This finding is surprising since a prediction of a behavioural shift towards the highest level of climate proaction seems to contradict the pessimism expressed in popular notions of China’s future commitments. The validity of this claim, however, depends, from the perspective of the unitary actor model, on the ratio between China’s actual future abatement costs and climate vulnerability.

5.1.3.3 FACTORING IN SIDE-PAYMENTS: THE CASE OF THE CDM

The analytical findings above represent Model A in its most stringent form where only abatements costs and climate vulnerability are assumed to shape the policy preferences of states. However, as noted by Sprinz & Vaahtoranta (2002) in a revision of their original framework, explanatory power can be increased by the inclusion of side-payments. In economics, side-payments is a term often used because the prospect of potential future gains (or fringe benefits) has the potential to affect the decisions of economic actors faced with cost-benefit ratios and thus, sway the outcome of a given situation by changing the incentive structure. For this reason, the present sub-section will analyse the likely gains attached to a proactive Chinese climate policy stance. The most prominent example of side-payments in the realm of global climate change are those accruing to countries engaging with the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). The CDM presents developing countries with an opportunity to harness the benefits of increased foreign direct investment at close to zero cost. Furthermore, through the completion of projects succeeding to reduce emissions, developing countries can earn revenue from selling certified emission reduction (CER) credits in international carbon markets134. Looking at China, the question is then to what extent the country stands to gain from engaging with the CDM.

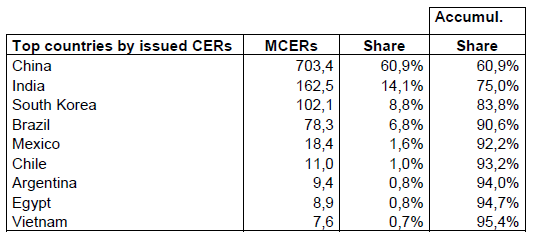

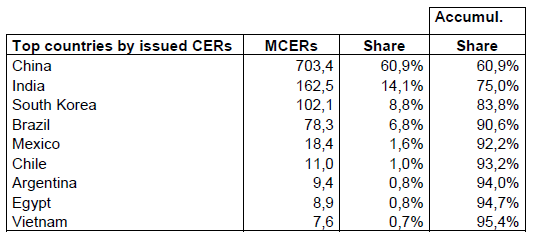

Since China’s accession to the Kyoto Protocol in 2005, the country has dominated the CDM. According to data from the Danish branch of the UNEP135 China dominates the CDM to such an extent that 61 percent of all CERs are issued to Chinese projects (see Figure 5.9).

Figure 5.9136

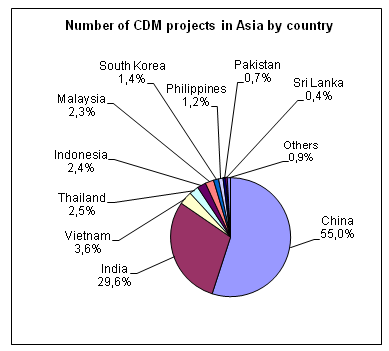

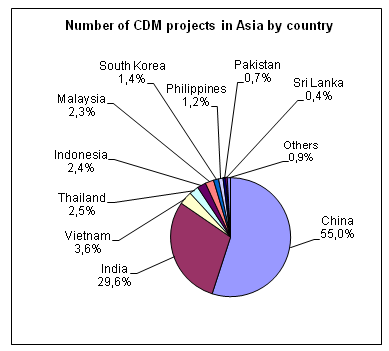

The Asian region alone accounts for 81 percent of all CDM projects and within this region China dominates equally heavy with 55 percent of all CDM projects being hosted here (see Figure 5.10).

Figure 5.10

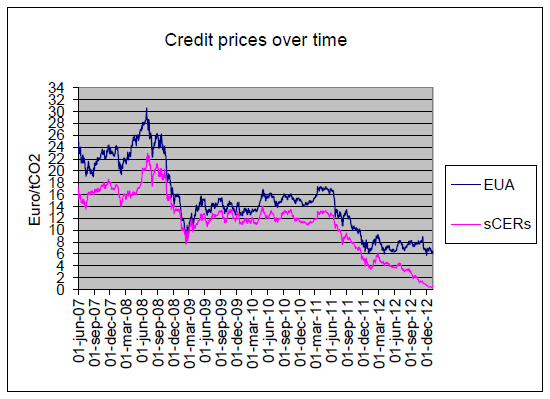

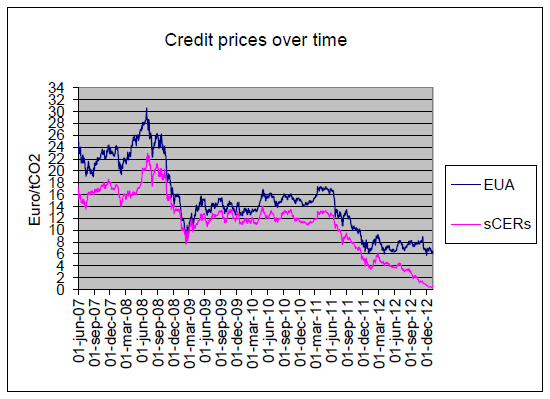

Despite a widespread Chinese domination of CDM project CDM revenue, however, still only accounts for a modest percentage of GDP. As detailed data for the issuance of CERs by host country are not publicly available my analysis relies on aggregate data from the secretariat of the UNFCCC. In their latest annual report Benefits of the Clean Development Mechanism137 (2012) it is estimated that CER revenue in China amounted to 5470 million USD138 for the period 2007-2011 (UNFCCC, 2012:90) which in terms of revenue per GDP amounts to only 0,02 percent of annual Chinese GDP on average. However, due to prolific price volatility in international carbon markets (see Figure 5.11) this percentage could rapidly increase as credit prices are currently at some of their lowest levels.

Figure 5.11139

Despite this, the likely side-payments flowing from the CDM mechanism to China are likely to increase rapidly in the future as carbon trading becomes more common place and more consolidated. Revenue from selling CERs, however, is only one out of several potential benefits to the Chinese economy from engaging with the CDM. According to Gang (2012), China also indirectly benefits in terms of attracting more FDI140 which is likely to reduce China’s long term costs of shifting to a more energy efficient economy. Particularly, the transfer of advanced climate technology from foreign companies working on CDM projects in China is one of major long term benefits of the CDM (Wang, 2010).

In absolute numbers, the total benefits per GDP to the Chinese economy from engaging with the CDM will, according to projections by the World Bank (2004), increase rapidly after 2010 (see Figure 5.12).

Figure 5.12141

Returning to my initial question of whether the CDM can be perceived as a side-payment capable of altering China’s climate incentives I find that based on China’s dominance of the CDM and the revenues flowing from the CDM this flexible mechanism is certainly a valid candidate. Although the current profits derived from selling CERs remain marginal due to low credit prices in primary and secondary carbon markets these revenues can be realised, nonetheless, at almost zero cost. Certainly, China has no immediate economic interest in disentangling itself from the CDM since the prolific price volatility in carbon markets could significantly raise the CER profits over a short period of time. Looking at Figure 5.11, credit prices in secondary markets were roughly four times higher prior to the onset of the current global financial crisis which indicates that these prices are likely to increase in the wake of the financial turmoil. However, more to the point China’s engagement with the CDM is a cost-effective way of securing a steady future flow of FDI and advanced technology which will ease the transition to a low-carbon economy. In that sense, the CDM presents China with a set of economic opportunities at no extra cost and, at least from the perspective of Model A, this is likely to further sway China’s climate policy in a more proactive direction.

5.1.4 INFERRING CAUSALITY BETWEEN X AND Y

The relevance of the results of the cost-benefit analysis above hinges centrally on the ability to infer causality between the included variables. Using Gerring’s (2004) terminology the question is whether the relationship between variables X (X1 and X2) and Y represents a causal mechanism. As there is no meaningful way in which a case study can systematically measure the strength of the association between variables its comparative advantage lies with the ability to uncover causal mechanisms i.e. “X must be connected with Y in a plausible fashion (...)” (Gerring, 2004:348). In order to assess whether the changes in China’s national interest do in fact cause changes in China’s climate policy two basic criteria must be met (de Vaus, 2001). Firstly, co-variation (1) must be present: If two factors are causally related they must at least be correlated; and secondly it must make sense (2): any assertion that co-variation reflects a causal relationship must be plausible.

(1) Co-variation:

Dependent variable: Within the time frame of the present dissertation China’s climate policy has gradually exhibited higher levels of climate policy proaction/ambition. From relatively low levels of ambition prior to the launch of the 11th FYP (2006) and the NCCP (2007) China’s climate policy currently encompasses a comprehensive and broad set of climate-related policies with ambitious quantitative targets.

Independent variable: As has been mentioned elsewhere142, the temporal disjunction between current and future damage costs of changing climatic conditions might at first glance represent a methodological problem in terms of inferring causality. However, this methodological contingency can be resolved by assuming that Chinese policy-makers are aware of the fact that policy actions today will have ramifications for the magnitude of future climate costs, thus making the distinction between current and future costs less obvious. Certainly, Chinese policy-makers have been under an increasing pressure to recognise the tangibility of global climate change as advocated by both domestic and international climate scientists alike (Wübbeke, 2010). Although the exact sequencing of events is less clear than in the case of China’s climate policy the perceived costs/benefits produced by climate change is generally agreed to have changed in 2005 (Hallding et. al. 2009a; Stensdal, 2012a), which temporally is just prior to the launch of China’s 11th FYP. From then on, perceptions of real and anticipated climate vulnerability have been gradually consolidating in tandem with mounting scientific evidence of global climate change.

The development of both variables would suggest, at least, that the dependent and independent variable are correlated. As perceptions of climate vulnerability have increased so has the level climate policy proaction. Conversely, at the start of the period in question both variables were at a low level.

(2) Plausibility:

Determining the plausibility of a causal association between X and Y further rests with two criteria (de Vaus, 2001). Firstly, in order to ascertain the existence of causality the time-order requires that the change in the independent variable precede changes in the dependent variable. As has been demonstrated above, X and Y in this study are correlated but more importantly X comes prior to Y. China’s climate policy started shifting only after the Chinese government’s perception of China’s climate vulnerability started to gradually change, and with it its perceptions of China’s national interest, in the period between 1998 to 2005.

Secondly, the plausibility of a suggested causal relationship hinges on this relationship being theoretically coherent. In other words, it must make sense from the perspective of theory. Based on the tenets of Model A I find that this criterion has been fulfilled since it logically makes sense to assert, as the unitary actor does, that countries will respond rationally to changes in its external environment. Global climate change fundamentally changes the conditions for securing future economic development across the world’s nations. In that respect, it would seem odd if countries did not as a minimum try to mitigate these changes by way of altering their respective climate policies so as to reduce the likely impact of a changing external environment.

Based on the criteria necessary to ascertain causality I would argue that China’s national aggregated interest does in fact exert a causal influence China’s climate policy. More specifically, the causal association exhibits signs of a positive correlation; the more China’s actual or perceived climate vulnerability increases, the more proactive China’s climate policy becomes. Although I cannot say anything meaningful about the strength (effect) of this relationship the causal association uncovered here can be characterised as representing a causal mechanism (Gerring, 2004).

5.1.5 SUMMARY – DIRECT CAUSALITY

Returning to the research question the first part of the analysis has provided evidence supporting a causal relationship between changes in China’s national interest and its subsequent climate policy. Based on a determination of China’s climate vulnerability and the costs associated with this vulnerability as well as China’s level of abatement costs the present analytical section has been able to calculate the cost-benefit ratio confronting China. This cost-benefit ratio between the actual and future costs of China’s climate vulnerability (i.e. the benefitsaction) and the costs of mitigating these would suggest that it is in the national interest of China, according to Model A, to act proactively in regards to global climate change. This finding is congruent with the recent shift in China’s climate policy characterised by an increased level of national climate policy ambition. In the short run, this shift has mainly been driven by changes to China’s national interest as a consequence of increases in China’s climate vulnerability. However, looking into the near future the analysis above would expect further increases in the level of China’s climate policy ambition due to China’s relatively low long term abatement costs combined with a sustained high level of climate vulnerability. This finding is particularly surprising as it contradicts the widespread western pessimism over China’s future climate policy stance. However, a higher future level of climate ambition is fully contingent on the actual cost-benefit ratio confronting China in the long term. Furthermore, the analysis above has also demonstrated that a proactive Chinese climate policy comes with additional benefits in terms of side-payments which have the potential to alter China’s initial cost-benefit calculations towards further increases in proaction. China’s engagement with international carbon markets under the auspices of the CDM is the most likely candidate of side-payments as the CDM holds the promise of a future steady flow of both FDI and technology transfer which are key in securing a low-carbon economy.

Recapping, China has primarily acted in accordance with the predictions made by the unitary actor model. However, despite this some variance is expectedly left unexplained. Most importantly, Model A fails to account for the fact that China has not exhausted its potential for climate policy proaction. Although China’s climate policy certainly embodies ambition this policy could however easily be even more ambitious143. In the stringent version of Model A one would expect China to exhaust its potential for ambition as only this situation fully satisfies the assumption of utility-maximisation characterised by the restoration of a stable equilibrium between costs and benefits. In other words, the analysis above fails to account for the fact that China’s current climate policy actually deviates slightly from its aggregated national interest. Model A cannot account for this empirical anomaly which I find warrants the inclusion of a theoretical framework better suited to shed some light on this unexplained variance. As argued elsewhere in this dissertation, countries do not always act as coherent unitary actors, as assumed by Model A, but will to some degree also be affected by dynamics taking place at the sub-national level. Following in this vein, I have argued that the interests of sub-national actors also impact the outcome of China’s climate policy. Namely, in a semi-authoritarian context such as the Chinese actors placed within or close to the official Chinese state apparatus are expected to exert the most influence on policy-making. For this reason, the analytical section below will seek to explain this mismatch by including dynamics in domestic Chinese politics.

5.2 INDIRECT CAUSATION – CHINA’S CLIMATE POLICY ENVIRONMENT

Given the analytical strategy of complementarity pursued in the present dissertation144, the aim of the present analytical sub-section is to analyse the unexplained variance which Model A fails to account for rather than compete to explain the same variance145. As emphasised by Rowlands (1995) the unitary actor model is a powerful analytical framework due to its parsimonious assumptions, however, this model cannot stand alone but needs to be complemented by theories capable of analysing domestic political dynamics in order to fully understand the climate policy choices of countries. As the previous analytical section elucidated China’s current climate policy actually deviates from its aggregated national interest which eludes the unitary actor model. Hence, I would argue that this mismatch warrants a complementary analysis of the dynamics created by sub-national actors by opening the ‘black box’ of China’s climate policy-making by utilising the domestic politics model (Model B). The relaxation of the stringent theoretical assumptions on which the unitary actor model is predicated makes the domestic politics model more capable of dealing with political complexity, thus enabling this model to explain policy outcomes that deviate from the national interest. According to Model B, policy outcomes depend on the conduciveness of a given policy environment which, in turn, depends on the configuration of interests (Z1) and relative power (Z2). Theoretically, I would only anticipate a conducive policy environment146 in the instance where the interests of the most influential climate policy actors converge with the contents of China’s aggregated national interest in terms of climate change. Therefore, the present analytical section will analyse whether the policy environment in which China’s climate policy-making is embedded can be characterised as conducive to climate policy proaction.

ANALYTICAL STRUCTURE

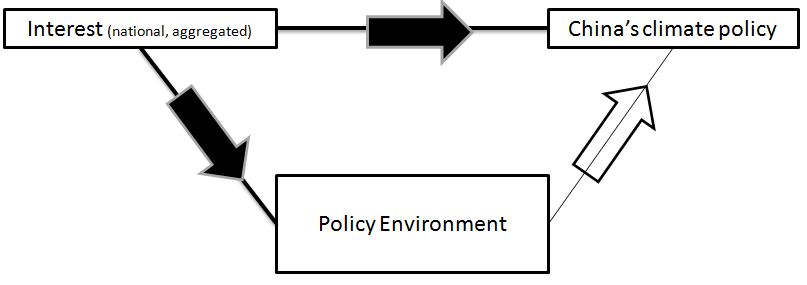

Returning briefly to the model of causality suggested in this dissertation (see Figure 5.13) this model will serve as the backdrop of the analytical structure pursued below.

Figure 5.13

The first analytical section (5.2.1) will elucidate the proposed causation between China’s aggregated national interest147 (X) and China’s domestic climate policy environment (Z) according to Model B. The second analytical section (5.2.2) will analyse the causal mechanism between China’s climate policy environment (Z) and the resultant climate policy outcome (Y). The third and last section (5.2.3) will, based on the analytical findings, assess whether the policy environment in which China’s climate policy-making process is embedded can be characterised as conducive to climate policy proaction.

5.2.1 X TO Z: THE POLITICAL IMPACT OF CHINA’S AGGREGATED NATIONAL INTEREST

The contents of China’s aggregated national interest will, according to Model B, influence China’s domestic policy actors through the distribution of costs and benefits. Depending on the organisational interests of the actors involved in China’s climate policy-making these actors will either stand to gain or lose from aligning China’s climate policy with the contents of the national interest. Actors standing to gain will, ceteris paribus, be inclined to ‘push’ for a policy outcome compatible with the national interest whereas actors standing to lose will seek to obstruct such policy moves. In turn, the propensity of policy actors to comply with the contents of China’s national interest depends on to what extent their organisational interests in the status quo148 are compatible with the national interest. As Conrad (2010) notes, organisational interests tend to supersede considerations over the contents of the national interest i.e. actors tend to act in accordance with a narrow set of organisational interests as these will contribute significantly more towards maximising utility than the diffuse set of national interests. This theoretical proposition has been succinctly formulated by Allison (1969:711) as: “Where you stand depends on where you sit”. Therefore, according to Model B, the resultant policy outcome of China’s climate policy-making process will be a simultaneous reflection of the compatibility of organisational interests of the actors involved in climate policy-making as well as their respective endowments of political power.

As substantiated by the previous analytical section it is increasingly in China’s national interest to respond ambitiously/proactively to climate change in order to reposition itself in a stable equilibrium. However, China’s climate policy response has so far remained insufficient to achieve such a stable equilibrium149. From the perspective of Model B the analytical questions are then to what extent the organisational interests of China’s primary climate policy actors are aligned with this national interest in the status quo and what the respective endowments of power are for these actors. The answer to both questions will be the focus of the analysis below.

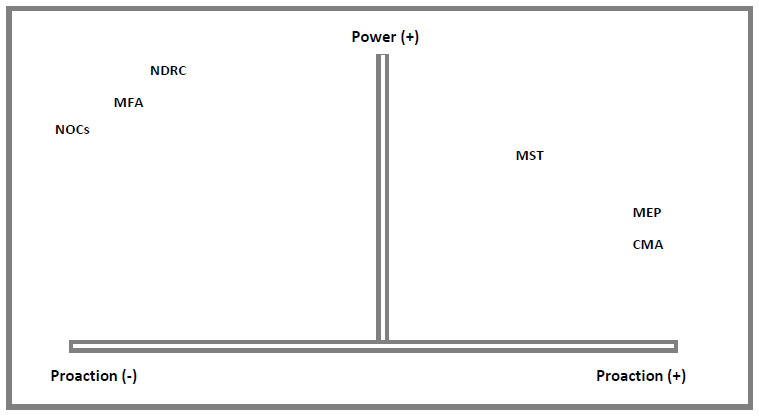

5.2.2 Z TO Y: CHINA’S CLIMATE POLICY-MAKING PROCESS – THE CONFIGURATION OF INTERESTS AND POWER

As has already been touched upon elsewhere, the proposed causal relationship between variables Z and Y as posited by Model B involves analysing the interests (Z1) and the relative political power (Z2) of the main policy actors involved in China’s climate policy-making process in order to assess whether China’s policy environment is conducive to climate policy proaction. Theoretically, the existence of a conducive policy environment requires that the interests of the most powerful policy actors are aligned with securing a proactive climate policy.

The present analytical section will be structured in the following way: The first sub-section will identify the main Chinese climate policy actors; the next two sub-sections will then analyse the interests (Z1) and political power (Z2) of these policy actors.

5.2.2.1 IDENTIFYING THE MAIN POLICY ACTORS IN CHINA’S CLIMATE POLICY-MAKING PROCESS

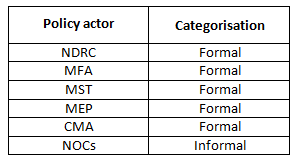

As China’s climate policy-making is likely to involve a multitude of policy actors across different political platforms and with varying degrees of significance I will for the present purposes focus the analysis on the actors which can be deemed primary actors150. For the sake of clarity, participating policy actors will be distinguished as either formal151 or informal152 policy actors.

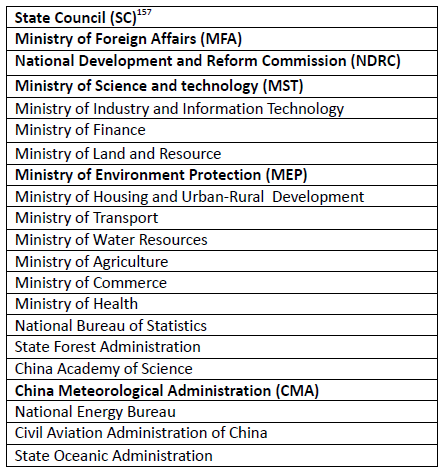

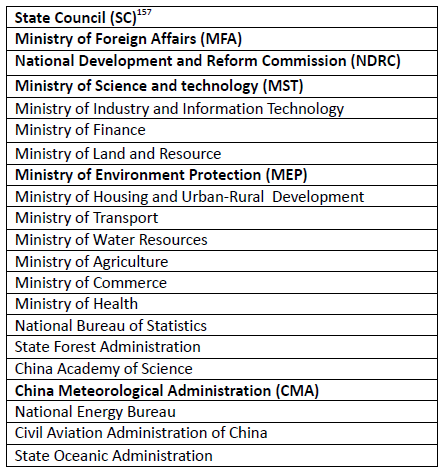

FORMAL ACTORS

According to China’s official Climate Change Info-Net153, the formulation of China’s climate policy takes place under the auspices of the National Leading Working Group on Addressing Climate Change (NLWGACC)154 155 headed by Premier Wen Jiabao reflected in the composition of the NLWGACC. The NLWGACC is tasked with coordinating policy among 21 government agencies (see Figure 5.14) in order to formulate a coherent climate change policy programme (Wübbeke, 2010).

Figure 5.14156

Although officially recognised as equally important it is clear that out of the large number of participating policy actors in the NLWGACC only a fraction of these can be considered primary climate policy actors. According to the secondary literature (Bjørkum (2005); Heggelund et. al. (2010); Gang (2012); Stensdal (2012b)), the policy actors in bold in Figure 5.14 are considered to be the primary policy architects behind China’s climate policy. This view is, at least, partly confirmed158 in an interview by China expert Jørgen Delman159.

INFORMAL POLICY ACTORS

Apart from the set of formal policy actors located inside the NLWGACC and thus embedded within the formal Chinese state apparatus Jørgen Delman also stresses the significance of policy actors located outside the formal sphere of political influence. Delman emphasises that due a chronic lack of government resources in terms of policy-making capacity, the Chinese government has fostered a policy-making tradition whereby outside actors are increasingly relied upon for inputs in the policy-making process. In the theoretical section160, however, it was argued that the inclusion of outside policy actors is an unintended consequence of the fragmented nature of Chinese political authority. I find it plausible to assume that both processes are likely to occur simultaneously but, nonetheless, invite different types of actors. The ‘bargaining loopholes’ created by fragmentation are most likely to invite weaker actors otherwise barred from political influence rather than stronger actors that have the capacity to exercise influence through more effective channels. Either way, the actors officially invited by the Chinese government to participate in the climate policy-making process will have a more effective political platform than those actors exercising discreet political influence. Hence, the focus will be on the former group of informal actors.

Within this group I would, based on Model B, assume that the most relevant sub-group is the faction of actors with most at stake in climate change politics. In terms of interests, commercial companies are the group of outside actors with most to lose from changing climate policies161. In particular, China’s group of large oil-producing companies162 have high stakes in the outcome of climate policy-making and are likely to resist any attempt to shift China’s climate policy in a more proactive direction since such a development would impede their ability to generate future profits. For instance, in the event of a proactive shift in climate policy the Chinese government is likely to seek to impact the incentive structure of the economy by shifting favourable productive conditions from one group of producers to another through the deployment of subsidies, concessional loans etc. In turn, this is likely to trigger a response from the producers currently favoured by the status quo. Hence, the group of NOCs can be considered the group of informal actors currently benefitting the most from the status quo and will consequently be most adversely affected by ambitious shifts in China’s climate policy. For this reason, the group of NOCs is included in the list of China’s primary policy actors.

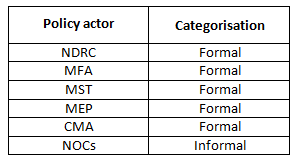

To recap, the group of policy actors involved in China’s climate policy-making has been narrowed down into a short list comprising both formal and informal primary policy actors (see Figure 5.15). These policy actors, their interests (Z1) and their relative power (Z2) will be the analytical focus of the subsequent sections.

Figure 5.15

5.2.2.2 Z1: INTERESTS

The configuration of interests in China’s climate policy-making process is a central variable in the domestic politics model as this variable carries with it behavioural implications. Depending on the interests of climate policy actors it becomes possible to predict, utilising Model B, the likely policy stances of these actors. According to Model B, it is assumed that policy actors will seek to maximise their respective interests through the course of the policy-making process. As has already been highlighted, the interests of actors consist of a combination of both national and organisational interests. Organisational interests will theoretically tend to supersede national interest in the process of interest aggregation unless the contents of the former converge with the contents of the latter. In this situation, the organisational interests of the policy actor is likely to amplify the national interest.

NDRC

The NDRC is tasked with the overall responsibility of running the Chinese economy. Its primary organisational mandate is to formulate and implement strategies related to China’s economic and social development (NDRC, 2012163) where its highest priority is to maximise economic development through sustaining high economic growth rates (Bjørkum, 2005). Looking over its official organisational statement available through the NDRC’s official website164 gives a good indication of the NDRC’s strong focus on economic development. In this mission statement the term economic development (or variations thereof) is mentioned repeatedly whereas the term climate change is scantily mentioned and only in passing at the very end of the list of objectives. This suggests that consideration of economic development weigh more heavily than considerations over the impact of climate change.

MFA

The MFA takes a similar position to that of the NDRC given that its main role has been to secure favourable international conditions for China’s economy through participating in international negotiations. Marks (2010) notes that “(...)it [MFA] has always given higher priority to economic development than environmental protection” (Marks, 2010:976). In the same vein, Heggelund et. al. (2010) characterise the MFA as a traditional “hardliner” in terms of its emphasis on economic considerations and sovereignty which resonates with the MFA’s official organisational objective of safeguarding “(...)national sovereignty, security and interests on behalf of the state”165. Thus, climate change as an issue is perceived from the perspective of safeguarding Chinese sovereignty as well as considerations over equity and not as inherently important in its own right.

MST

The MST has mainly been involved with the technical aspects of climate change in China as well as cooperating with scientific communities abroad. According to Heggelund et. al. (2010) the MST has the highest technical expertise of all the ministries involved in the NLWGACC, which becomes quite obvious looking at the educational backgrounds166 of the MST leadership. Most of the principal officials have a PhD within the natural sciences which is comparatively uncommon within the central Chinese administration167. The organisational objective of the MST is captured in a 2007 strategy paper168 on climate change drafted by the MST alongside other ministries working with climate change policies. In this paper, science and technology is recognised as immensely important not only to China’s domestic response to climate change but also for the sake of the economic opportunities provided by action on climate change. In the strategy paper, advances in science and technology are recognised as key in attaining “(...) sustainable socio-economic development, safeguarding the national interests, and fulfilling the international commitments” (MST, 2007:4). Particularly, safeguarding the national interests has a dual meaning as the strategy paper is both alluding, on the one hand, to the point that domestic Chinese climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts depend on advances within science and technology:

However, on the other hand, the MST sees a clear opportunity for China to profit on climate change developments abroad through technology transfer which lowers the cost of China’s mitigative efforts. Of these two simultaneous objectives technology transfer is likely to supersede the other as it, from the perspective of the MST, contributes more towards the attainment of China’s national interest. Economy (2001) also notes that the MST is interested in a “(...) more proactive climate policy in order to gain access to new technologies from abroad” (Economy, 2001:248). Despite favouring technology transfer over environmental protection the organisational interests of the MST are, nevertheless, different from those of the NDRC and the MFA since the MST prioritises environmental protection higher than both the NDRC and the MFA.

MEP

The most proactive stance on climate change is represented by the MEP. This organisation has undergone significant institutional changes throughout the last three decades since its inception in the start of the 1980s. Formerly known as the National Environmental Protection Bureau (NEPB) the organisation was renamed in 1988 as the National Environmental Protection Agency (NEPA). In 1998, NEPA was upgraded from semi-ministerial status to administration170 status and renamed the State Environmental Protection Administration (SEPA). The current organisation known as the MEP was created out of SEPA in 2008, thus according the MEP with full ministerial status. In the MEP’s mission statement the organisation seeks to “(...) Develop and organize the implementation of national policies and plans for environmental protection”171 in order to facilitate an “environment-friendly society”. Specifically in regards to climate change, the MEP is tasked with the responsibility of achieving the national emission reduction targets through the supervision of local government. The organisational interests of the MEP are the ones most aligned with taking a proactive stance on climate change as this organisation seeks to champion stringent regulation both in terms of environmental protection and climate change reduction. In other words, the organisational interests of the MEP are almost fully aligned with China’s national interests in terms of climate change.

CMA

The last of the formal primary climate policy actors in the NLWGACC is the CMA which until 1998 was the leading organisation regarding climate change policies. The CMA coordinated China’s initial response to climate change through close cooperation with the IPCC in the 1980s and 1990s. Later, however, when the focus of the Chinese government increased in terms of climate change, responsibility was shifted to the NDRC. Despite this, according to the CMA’s official website172, the organisation still retains some of its former tasks. Most notably, the CMA is a scientific liaison to the NDRC and the MFA much like the role played by the MST. Also, the CMA together with the MEP and the MST has been one of the key architects behind the assessment reports examining the potential adverse impact of climate change in China. Therefore, given the prominent position of expertise within this organisation, its interests are likely to be aligned with those of the MEP and the MST thus favouring policies taking a proactive stance on climate change mitigation.

NOCS

Although the group of NOCs are under the formal control of the Chinese government research has shown that due to the increased marketization and globalisation of the Chinese energy sector the NOCs have managed to gain autonomy from and influence on the Chinese political system (Downs, 2007; Tu, 2012). Or as one report bluntly puts it: “They [NOCs] are owned (mainly) by the state, but not run by the state” (IEA, 2011:25). Downs (2007) notes that in Chinese political discourse the NOCs are increasingly considered a “monopolistic interest group” which is problematic as: “(...) their [the NOCs] domestic and international interests do not always coincide with those of the party-state” (Downs, 2007:122). In fact, the group of NOCs have in recent years started to exhibit behavioural dynamics similar to those of the private company lobbying for a favourable business environment. The global activities of the NOCs have caused these to act as their private counterparts in many other countries. Most importantly, the NOCs recognise that the cornerstone of any successful business strategy is seeking to establish the most favourable business environment which, in turn, will maximise their profitability. Viewed from the perspective of climate change mitigation, a proactive stance on climate change will, ceteris paribus, be deleterious for the NOCs ability to accrue large future profits as production costs are likely to increase. Therefore, this group of policy actors will largely have interests aligned with securing a favourable business environment which is best achieved through the adoption of an unambitious climate policy.

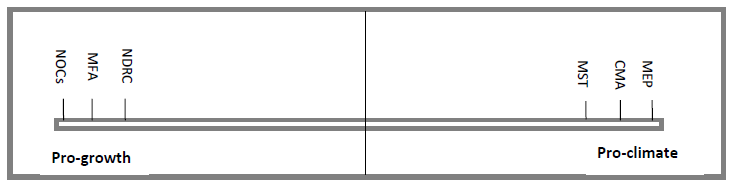

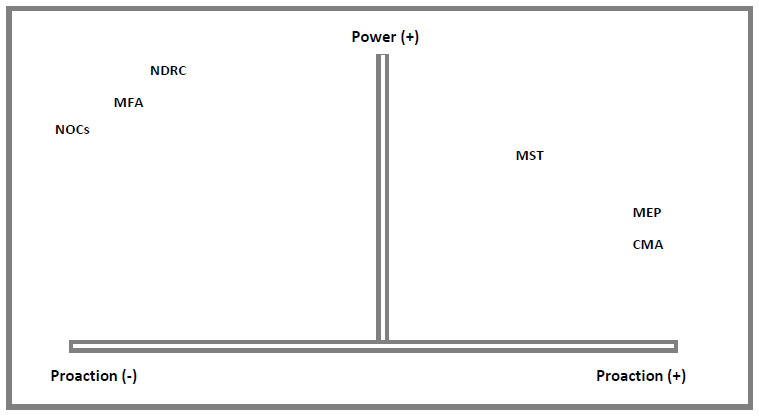

THE PRO-CLIMATE OR PRO-GROWTH DIVIDE

The configuration of interests of China’s primary policy-making actors reveals a tangible cleavage (see Figure 5.16) reflected by the fact that policy actors have diverging interests in terms of the emphasis placed on either economic concerns or climate concerns. On the one hand, are those actors with organisational interests aligned with what can reasonably be characterised as pro-growth policies. However, on the other hand, such interests are countervailed by actors pursuing interests which can best be characterised as pro-climate policies.

Figure 5.16

Although Figure 5.16 is a simplified representation, it does however point to the fact that clear interest divergences exist among China’s primary policy-makers thus clustering these into factions. On the one hand, the policy actors whose interests are least aligned with ‘pro-climate’ policies are those government agencies tasked with securing favourable economic growth conditions. In this group, we find the NDRC which has the overarching responsibility of safeguarding the viability of the Chinese economy and the MFA which strive for favourable international economic conditions. Both actors have a political mandate to sustain high economic growth rates and are unlikely to favour a more proactive climate policy. Spearheading the cluster of pro-growth protagonists, however, are the NOCs as China’s large oil-producing companies is the group of ‘outside’ actors with interests most clearly opposed to efforts aimed at climate change proaction. Climate change proaction is likely to reduce the profitability of these companies as government investments will be shifted to green-tech industries, thus pitting the interests of this group squarely against any attempts at lifting the level of climate ambition. On the other side of the political divide are those actors with interests aligned with pro-climate policies. The MST is the actor in the pro-climate cluster with interests most in line with the interests of the actors in the pro-growth cluster given that the MST perceives climate mitigation as a necessary means to an end. In other words, through the advancement of S&T, the MST strives to make the Chinese economy more profitable less so than aiming to save the environment as some of the other actors in the pro-climate cluster. That MST recognises that supporting policies aimed at climate change mitigation will secure more favourable conditions for the organisation to exert influence on future policies as climate proaction will more than likely increase organisational funds. Further towards the right in Figure 5.16 one finds the cluster of pro-climate actors proper in the form of the CMA and the MEP. The CMA has, given its high level of scientific expertise, been instrumental in coordinating scientific efforts aimed at assessing China’s climate vulnerability making this organisation inclined to favour policies seeking climate change proaction. However, the CMA is also in some respects a ‘scorned’ organisation given the loss of its former prominent bureaucratic position in the institutional reshuffle in 1998, where the responsibility of climate change was officially shifted to the NDRC. Since 1998, however, the CMA has remained a marginal bureaucratic actor but the elevation of climate change as a policy issue of national concern presents a unique opportunity for the CMA to restore some of its former prominence by making itself indispensable to efforts aimed at climate change mitigation. The MEP is the government agency with interests most aligned with pro-climate policies as the official mandate of the MEP is to provide environmental protection and securing an ‘environment-friendly society’. This, in turn, fits well with climate proaction given that efforts aimed at reducing GHG emissions will serve to simultaneously reduce environmental strain and mitigate climate change.

According to Model B, the status quo configuration of interests matters in as much as it will have ramifications for the likely policy stances of actors in response to the contents of China’s national interest. As the previous main analytical section substantiated it is increasingly in China’s aggregated national interest to adopt policies aimed at climate change mitigation (i.e. pro-climate policies). The likely response of actors then depends on the compatibility between their status quo interests and the contents of the national interest. In the status quo actors with interests aligned with the national interest will stand to gain and, conversely, the actors with interests diverging from the national interest will stand to lose. Hence, the MEP, the MST and the CMA all stand to gain from a higher priority assigned to climate change mitigation efforts in terms of bureaucratic status, portfolio of responsibilities and increased budgets. On the other hand, the NDRC, the MFA and the NOCs stand to lose as these will, conversely, lose bureaucratic standing and profitability respectively. Therefore, I would anticipate the pro-climate faction to actively endorse a proactive/ambitious climate policy as this would ensure utility-maximisation for this group of actor whereas a similar policy stance would be detrimental to the utility-maximising efforts of the pro-growth faction and hence foster resistance.

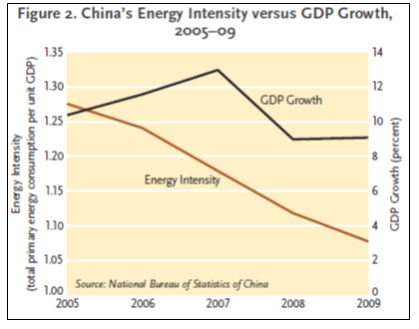

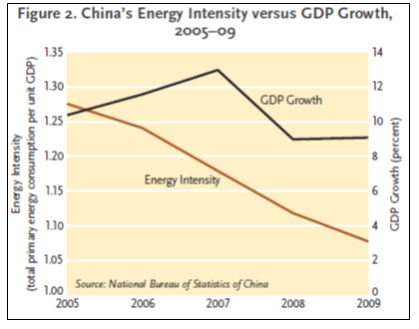

It should, however, be noted that the degree of interest compatibility between organisational interests and the national interest is also partly determined by the extent to which efforts aimed at climate change mitigation can be reconciled with efforts to secure economic growth. Given China’s low energy efficiency (Delman & Odgaard, 2011) (i.e. high energy intensity) securing high economic growth rates, in the status quo, can only be achieved through high GHG emission rates. This means that those policies aimed at climate change mitigation (i.e. proactive climate policies) will in the status quo be irreconcilable with policies aimed at securing economic growth (i.e. pro-growth policies). Therefore, in the case of China I would anticipate the interest divide separating policy actors to be further consolidated, thus causing the policy responses of actors to amplify.

5.2.2.3 Z2: DISTRIBUTION OF POWER

The distribution of power among the policy actors participating in China’s policy-making process is vital to understanding resultant policy outcomes. Particularly, relative political power (or influence) is a key variable when predicting which set of interests is likely to shape policies. Ideally, we would expect the course of a policy process to incorporate as many interests as possible, however, the domestic politics model asserts that when faced with ‘hard choices’ policy actors tend to strive for policies that favour their narrow set of preferred interests even if pursuing these are sub-optimal from the perspective of national interests. In terms of China’s climate policy-making this is a particularly salient point to make given the tangible interest divide existing between pro-growth and pro-climate protagonists. When interests are so clearly pitted against each other as in the case of China the configuration of political power becomes vital for the prediction of outcomes. According to the assumptions of Model B, the distribution of power will favour some interests over others as the interests of the most powerful policy actors will tend to overshadow the interests of their weaker counterparts.

The analytical sub-section below will turn again to the primary actors of China’s climate policy-making and investigate the relative influence of these on the climate policy-making process.

NDRC

The NDRC is one of the highest-ranking bureaucratic bodies within the Chinese central administration and comprises many different sectoral departments related to economic development and energy which reflect the coordinating status of this actor. Formerly known at the State Planning Commission (SPC) the NDRC is considered to be the single “(...) most influential governmental agency in the fields of economy, energy, and climate change (...)” (Heggelund et. al., 2010:237). Some even go as far as characterising the NDRC as a ‘super-ministry’ (Lawrence & Martin, 2013; Interview) which given the large portfolio of responsibilities is probably an accurate description. However, the political power of the NDRC is somewhat mitigated by the fact that this ‘super-ministry’ only has staff amounting to 890173 civil servants spread across 26 functional departments causing a lack of capacity. Given that the NDRC is tasked with the mammoth task of overseeing all aspects of the Chinese economy the limited amount of staff makes the NDRC highly dependent on the supply of capacity from both actors located outside and inside the Chinese state apparatus which at least partially offsets the power of this bureaucratic leviathan (Interview).

MFA

The MFA, given its ministerial status, ranks just under the NDRC in terms of bureaucratic influence174 but rises above the other ministries involved in the NLWGACC in terms of real political influence (Wübbeke, 2010). One of the MFA’s main sources of influence is that it has been instrumental in safeguarding China’s sovereignty, which is recognised as one of the top-priorities of the Chinese leadership (Schreurs & Economy, 1997). Also, the role as China’s lead negotiator in international affairs speaks to the influence of this policy actor. In terms of climate change negotiations, the MFA has been present at all the COPs175 and has served as lead negotiator in all of these. In regards to the NDRC, the MFA has managed to capitalise on its close relationship with the NDRC as these two organisations share a considerable interest overlap176 resulting in cooperative relationships rather than bureaucratic competition between two almost equally powerful entities. Apart from slight tensions at the COP15 on how to proceed in the negotiations, the MFA and the NDRC has formed what can be characterised as a partnership (Interview) in recent years consolidating the influence of both organisations.

MST

Given the MST’s high level of scientific expertise this agency has been one of the main actors in the continuous assessments of the adverse impact confronting China as a result of changing climatic conditions. Formally, the MST acts as a scientific liaison to both the NDRC and MFA thus placing the MST closer to the ‘inner’ circle of influence compared to other like-minded agencies on the other side of the pro-growth/pro-climate divide. Therefore, the MST can be considered a fairly influential policy actor under the auspices of the NLWGACC and its strong scientific profile can be argued to represent its strongest card when confronted by more powerful organisations such as the NDRC and the MFA.

MEP

In terms of political influence on the climate policy-making process the MEP has historically been regarded as a weak bureaucratic actor (Bjørkum, 2005). Although, the recent upgrade to full ministerial status has accredited this organisation with more formal power there are still large discrepancies in the political influence exerted by the MEP and significantly more powerful agencies such as the NDRC. As Jørgen Delman notes, there is still a long way before the MEP can “take on the NDRC”. In fact, in the process of vying for influence on the formation of policies regarding environmental protection and climate change the MEP has often found itself superseded by other actors with the same hierarchical rank (Interview). The best example of this is the continuous undermining of influence exercised at lower administrative levels (Gang, 2009). Here, local representatives of the MEP seeking to financially sanction polluting companies are countervailed by efforts of local representatives of the NDRC. More often than not, the NDRC will reduce the taxation of sanctioned companies equal to the size of the environmental fine. Despite this, Conrad (2010) notes, however, that this inferior position might be slowly changing as the MEP is increasingly perceived as “(...) one of the most dynamic and publicly visible bureaucratic entities in China (...)” (Conrad, 2010:61). Conrad predicts that this might create a situation whereby the MEP manages to amass influence within the broader realm of environmental protection and climate change mitigation.

CMA

As with the MST the main source of political influence of the CMA is derived from its high level of scientific expertise. The CMA together with the MEP and the MST has been a key architect behind the assessment reports examining the potential adverse impact of climate change in China. According to Conrad (2010), the influence of the CMA has primarily been shaped by its former director Qin Dahe who in his capacity as one of China’s leading climatologists managed to wield some influence on organisations significantly more politically powerful than the CMA. Qin Dahe is known for having advocated stringent emission reduction and considers climate change a matter of ‘moral responsibility’177. Little is known, however, about the stance on climate change taken by the current director Zheng Guoguang but given the CMA’s hierarchical ranking as an ‘administration’178 its influence is likely to be limited compared to that of the NDRC and the other primary policy actors of the NLWGACC.

NOCS