Conclusion

By Kasper Sulkjær Andersen

This article is a part of a master's thesis from 2013.

6.0 CONCLUSION

In the preceding sections, China’s climate policy in the period spanning the three most recent FYPs (2001-2012) has been analysed in accordance with the nature of the research question. The present concluding section is comprised of two main elements: firstly, the results of the analysis will be presented and secondly the utilised method and theory will be assessed.

6.1 EXPLAINING AN INCREASINGLY AMBITIOUS CHINESE CLIMATE POLICY

The present dissertation has been driven by the following research question:

How can the increased level of ambition in China’s national climate policy be explained?

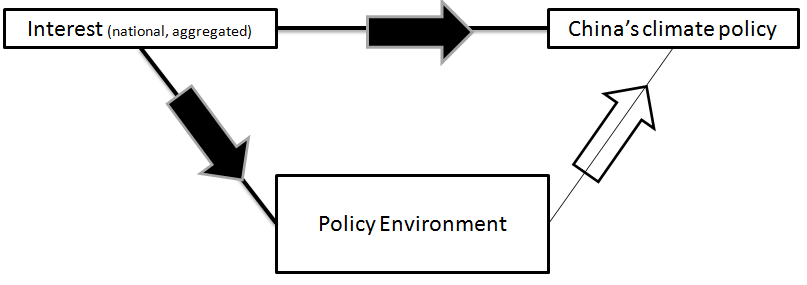

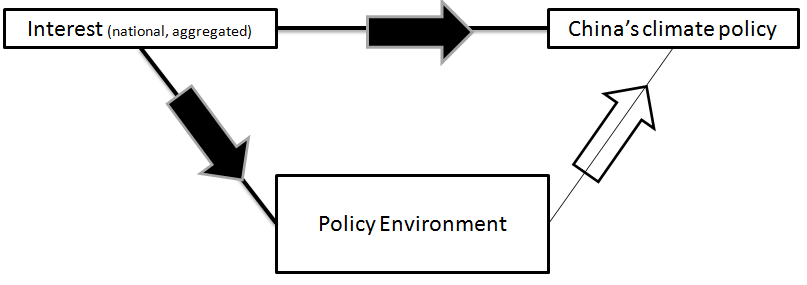

The analysis of this research question was facilitated by the utilisation of two exponents of interest-based theory. The first analytical section (Section 5.1) utilising the unitary actor model found that China’s increasingly ambitious climate policy can be explained as a rational response to shifting Chinese interests. More specifically, the analysis found that China is confronted by a cost-benefit ratio in favour of climate policy proaction since the costs of climate inaction are likely to be substantial and far outweigh the costs of action. Therefore, China’s policy response can be plausibly inferred as representing the utility-maximising efforts of a rational, unitary policy actor. However, the analysis also found that so far China’s response has not been optimal from an economic perspective as one would expect China’s climate policy to be even more ambitious. Given the analytical strategy of complementarity pursued here and the nature of the proposed causation, the second analytical section (Section 5.2), sought to answer the question regarding why this discrepancy exists between China’s actual and ideal climate policy efforts as explaining this is integral to fully comprehend the ambitious shift in China’s climate policy. Through the utilisation of the domestic politics model, the second main analytical section found that the policy environment in which China’s climate policy is embedded can be characterised as unconducive in the status quo (i.e. the organisational interests of China’s most powerful climate policy actors are opposed to climate policy proaction). This unconducive policy environment, in turn, effectively acts as a constraint on China’s climate policy response (see Figure 6.0) which explains why this response has been economically sub-optimal. However, the second part of the analysis also demonstrated that China’s policy environment is increasingly exhibiting signs indicative of a higher degree of conduciveness which has the potential to amplify future policy responses. The analysis anticipates these effects to manifest already by the launch of the 13th Chinese five-year plan in 2015.

Figure 6.0

6.2 ASSESSMENT

6.2.1 METHODOLOGY

Given the transdisciplinary method utilised to generate the results of the first analytical section, the main point of contestation is the uncertainty inevitably attached to research dealing with global climate change. In particular, the exact sequencing and timing of the adverse natural events facing China are hard to accurately gauge given that global climate change is the result of a highly complex web of causality between dynamics taken place at the micro-, meso- and macro-level. Also, the actual climate impact on different countries is very complex to measure given the temporal disjunction between current actions and future consequences185. In effect, the level of complexity involved in climate change impairs the ability of the researcher to accurately predict future climatic events. In order to mitigate this methodological issue, the present dissertation has relied upon the findings of authoritative climate change research. Furthermore, when calculating the actual and future costs of China’s climate vulnerability the present study has utilised conservative estimates so as to avoid an artificial inflation of the results of the analysis.

6.2.2 THEORY

As with the application of all theory the set of interest-based theories utilised here comes with their own set of limitations and analytical ‘blind spots’. Most importantly, interests-based theory being predicated on economistic assumptions will be biased towards favouring a priori economic interests and the influence of traditional policy actors186 – thus, largely corresponding to the bias inherent in the majority of rationalistic theory. This bias, in turn, causes rationalistic theories to downplay or outright omit more subtle causes of policy change which more recent studies187 of China’s climate policy accredit transformative capacity. In hindsight, I would argue that the inclusion of reflectivist theory has the potential to enhance the overall explanatory power of the present dissertation. In particular, I would contend that the insights provided by the literature on epistemic communities (Haas, 1989) and social learning processes (Underdal, 1998) are salient in the case of China given that China’s political elite is increasingly exposed to both international as well as domestic climate experts (Wübbeke, 2010). In turn, the heightened contact with expertise is likely to at least partially affect the perceptions and thereby interests of the Chinese leadership through social learning mechanisms. Therefore, the analysis of China’s climate policy would benefit from the inclusion of more social-constructivist elements emphasising norms, identity and ideas.

This article is a part of a master's thesis from 2013.

| < Analysis | Table of Contents | References > |

6.0 CONCLUSION

In the preceding sections, China’s climate policy in the period spanning the three most recent FYPs (2001-2012) has been analysed in accordance with the nature of the research question. The present concluding section is comprised of two main elements: firstly, the results of the analysis will be presented and secondly the utilised method and theory will be assessed.

6.1 EXPLAINING AN INCREASINGLY AMBITIOUS CHINESE CLIMATE POLICY

The present dissertation has been driven by the following research question:

How can the increased level of ambition in China’s national climate policy be explained?

The analysis of this research question was facilitated by the utilisation of two exponents of interest-based theory. The first analytical section (Section 5.1) utilising the unitary actor model found that China’s increasingly ambitious climate policy can be explained as a rational response to shifting Chinese interests. More specifically, the analysis found that China is confronted by a cost-benefit ratio in favour of climate policy proaction since the costs of climate inaction are likely to be substantial and far outweigh the costs of action. Therefore, China’s policy response can be plausibly inferred as representing the utility-maximising efforts of a rational, unitary policy actor. However, the analysis also found that so far China’s response has not been optimal from an economic perspective as one would expect China’s climate policy to be even more ambitious. Given the analytical strategy of complementarity pursued here and the nature of the proposed causation, the second analytical section (Section 5.2), sought to answer the question regarding why this discrepancy exists between China’s actual and ideal climate policy efforts as explaining this is integral to fully comprehend the ambitious shift in China’s climate policy. Through the utilisation of the domestic politics model, the second main analytical section found that the policy environment in which China’s climate policy is embedded can be characterised as unconducive in the status quo (i.e. the organisational interests of China’s most powerful climate policy actors are opposed to climate policy proaction). This unconducive policy environment, in turn, effectively acts as a constraint on China’s climate policy response (see Figure 6.0) which explains why this response has been economically sub-optimal. However, the second part of the analysis also demonstrated that China’s policy environment is increasingly exhibiting signs indicative of a higher degree of conduciveness which has the potential to amplify future policy responses. The analysis anticipates these effects to manifest already by the launch of the 13th Chinese five-year plan in 2015.

Figure 6.0

6.2 ASSESSMENT

6.2.1 METHODOLOGY

Given the transdisciplinary method utilised to generate the results of the first analytical section, the main point of contestation is the uncertainty inevitably attached to research dealing with global climate change. In particular, the exact sequencing and timing of the adverse natural events facing China are hard to accurately gauge given that global climate change is the result of a highly complex web of causality between dynamics taken place at the micro-, meso- and macro-level. Also, the actual climate impact on different countries is very complex to measure given the temporal disjunction between current actions and future consequences185. In effect, the level of complexity involved in climate change impairs the ability of the researcher to accurately predict future climatic events. In order to mitigate this methodological issue, the present dissertation has relied upon the findings of authoritative climate change research. Furthermore, when calculating the actual and future costs of China’s climate vulnerability the present study has utilised conservative estimates so as to avoid an artificial inflation of the results of the analysis.

6.2.2 THEORY

As with the application of all theory the set of interest-based theories utilised here comes with their own set of limitations and analytical ‘blind spots’. Most importantly, interests-based theory being predicated on economistic assumptions will be biased towards favouring a priori economic interests and the influence of traditional policy actors186 – thus, largely corresponding to the bias inherent in the majority of rationalistic theory. This bias, in turn, causes rationalistic theories to downplay or outright omit more subtle causes of policy change which more recent studies187 of China’s climate policy accredit transformative capacity. In hindsight, I would argue that the inclusion of reflectivist theory has the potential to enhance the overall explanatory power of the present dissertation. In particular, I would contend that the insights provided by the literature on epistemic communities (Haas, 1989) and social learning processes (Underdal, 1998) are salient in the case of China given that China’s political elite is increasingly exposed to both international as well as domestic climate experts (Wübbeke, 2010). In turn, the heightened contact with expertise is likely to at least partially affect the perceptions and thereby interests of the Chinese leadership through social learning mechanisms. Therefore, the analysis of China’s climate policy would benefit from the inclusion of more social-constructivist elements emphasising norms, identity and ideas.

| < Analysis | Table of Contents | References > |

Posted by branner

on 24. May 2014, 17:09 0 comment(s) · 2303 views

Comments

No comments yet.

Join the debate on Conclusion:

Related content

| Threads | Replies | Last post |

| I have come to the conclusion CO2 is irrelevant | 1 | 07-09-2016 23:57 |