Theory

By Kasper Sulkjær Andersen

This article is a part of a master's thesis from 2013.

2.0 THEORY

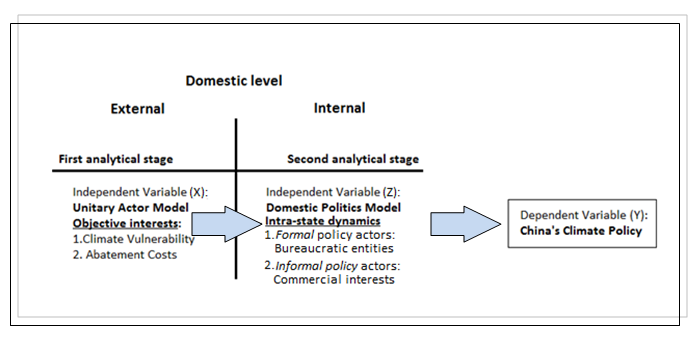

As mentioned above, focusing on the significance of interests is a useful starting point for the analysis of climate politics. Global climate change is at its most basic ultimately about interests since changing climatic conditions have the potential to (re-)distribute benefits and assign costs to different actors, thus affecting their preferences. In the context of China, an assertion of the significance of interests is particularly valid since climate change is intimately linked with the prospects of securing continued economic growth which, in turn, has ramifications for political stability. The (re-)distributive process caused by climate change takes place both between and within countries. In the introduction I argued that in the case of China, dynamics at the domestic level take primacy in the formulation of China’s climate policy due to, among other things, a strict adherence to the principle of sovereignty. As a result of this, the Chinese process of redistribution will primarily be couched in domestic terms which warrant an analytical focus on domestic factors. The conjunction of domestic factors shaping China’s climate policy will be analysed employing two complementary yet distinct theoretical models. Both models, however, emphasise the importance of interests in the formation of climate policy but operate at different analytical levels. By combining the respective insights of both models facilitates a more comprehensive explanation of the recent shift in China’s climate policy.

2.1 INTEREST-BASED THEORY37

The group of interest-based theories shares a similar starting point in terms of the assertion that interests38 matter for outcomes of foreign policy. Just as the famous assertion made by neoliberal institutionalists39 that “institutions matter” in international politics so does the group of interest-based theory stress that (national) interests matter when governments decide on which foreign policy to adopt.

Underlying interest-based theories is a shared set of core assumptions40 emphasising that interests matter because these inform and carry with them behavioural implications. It is assumed that actors have the ability to hold several and competing interests and rank these in accordance with their respective contribution to utility-maximisation. This assumption has behavioural implications as interest-based theory assert that when faced with a decision, an actor will choose the action or set of actions most aligned with its ranked interests. Central to this are the respective costs and benefits of different sets of actions. Given that the actor is rational and utility maximising interest-based theory would predict that faced with a choice an actor will choose the action with most benefits and least costs. Rationality also entails that actors are assumed to be susceptible and responsive to new information about future costs and benefits in order to avoid short term gains at the expense of larger future gains.

Depending on both the nature of the political issue in question, as well as characteristics pertaining to the actor (individual, firm, country etc.) involved, the set of core assumptions can be either tightened or relaxed in order to fit the context in question. In the case of climate change policy, interest-based theory is most often employed at the aggregate level, treating the state is a unitary actor faced with a set of national cost and benefits from which net benefits can be derived (Dietz et. al., 2012). However, in reality, countries seldomly function as fully unitary or fully rational entities, but are influenced by factors embedded within the domestic political context. Different competing pressure groups will seek to influence the policy-making process in order to achieve their set of exclusive interests. Furthermore, government agencies will compete in order to enhance their organisational budgets and increase their prominence through expanding the portfolio of responsibilities, thus influencing the policy-making process. For these reasons, the present dissertation includes two interest-based explanatory models. Where the first model (Model A) conceives China’s climate policy as the result solely of China’s aggregated national interest, the second model (Model B), building on Model A, includes the influence of domestic factors relevant to the political landscape in China.

2.1.1 MODEL A: THE UNITARY ACTOR MODEL

The unitary actor model41 is an interest-based explanatory approach to foreign policy decision-making where actions of foreign policy are conceptualised as the result of the unitary state acting strategically towards the attainment of its national objectives or as a response to an external threat. The model starts with the basic assumption of the state as a self-interested unitary actor endowed with the ability to act rationally. It is assumed that the behaviour of the state actor is chiefly motivated by a desire to achieve its national interests which are assumed to be objectively given. The unitary state actor will strive to achieve its national interest as these will increase the likelihood of state survival. Given the rationality of the state it is further assumed that the state has the ability to make rational choices vis-a-vis its national interests. In other words, the unitary state will choose the foreign policy option which has the lowest costs and maximum gains depending on such conditioning factors as the values assigned to different national policy objectives; alternative courses of action and the various sets of consequences (Allison, 1969). It is further assumed that the state has or can obtain perfect information regarding its national interest. No matter how complex reality is, the unitary actor model posits that accurate cost-benefit analyses are always possible to conduct from the perspective of the unitary state actor.

Applied to the case of China, the unitary actor model in its purest form, as elucidated above, would start out by defining China’s overall national interests as these dictate options across policy areas. In the case of China, taking primacy are concerns over the continued survival and integrity of the Chinese political regime which, in turn, rest squarely on maintaining sovereignty and economic development. From this view, climate policy does not factor into the equation since climate policy falls outside the immediate scope of what constitutes national interests despite indirectly impacting on the likelihood of attaining national interests.

For this reason, the unitary actor model proper needs to be slightly augmented in order to encompass climate policy dynamics. This modified version of Model A questions the assumption that climate change lies outside of national interest. Instead, it assumes that climate change fundamentally alters the cost-benefit ratios of the unitary state actor.

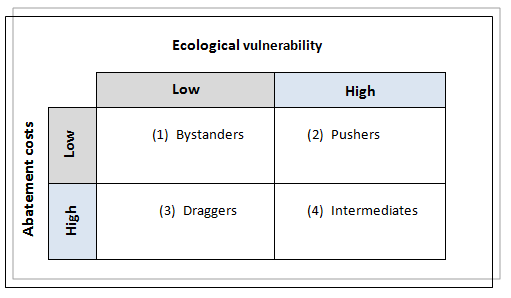

2.1.1.1THE INTEREST-BASED EXPLANATION OF INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY

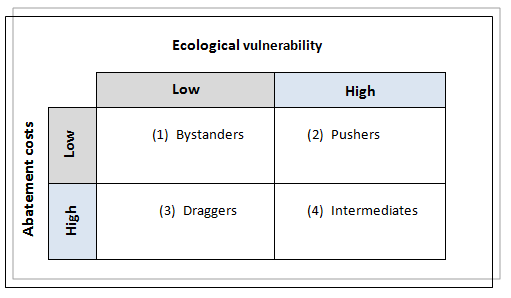

The slightly modified version of the unitary actor model, dubbed the “Interest-Based Explanation of International Environmental Policy” (Sprinz & Vaahtoranta, 1994), makes parallel assumptions to the unitary actor model. However, setting it apart is an assumption that what constitutes national interests will differ according to the situational context. Overarching national interests such as sovereignty and survival are obviously assumed to be important but depending on the situational context the nature of what constitutes national interests will vary. Sprinz & Vaahtoranta (1994) argue that the environmental politics of different countries mirrors their immediate national interests within the context of the environment. The overarching national interests will then serve as guidelines to what can feasibly be perceived as a given country’s interests i.e. the immediate interests within a given situational context are assumed to be aligned with the country’s overall national interests. Following from this, within the context of environmental foreign policy, what matters is a country’s level of ecological vulnerability42 and abatement costs43. The model suggests that countries will 1) seek to “(...) avoid vulnerability (...)” (Ibid:78) and that 2) “States are more inclined to participate in environmental protection when the costs of compliance are relatively minor” (Ibid:78ff). Based on these behavioural assumptions, the interest-based model suggests that countries will act as either “pushers”, “draggers”, “bystanders”, or “intermediates” (see Figure 2.0) depending on the cost-benefit ratios related to their respective levels of vulnerability and abatement costs. States will act as “pushers” (seeking stringent/proactive environmental foreign policy) when their combined ecological vulnerability is high and abatement costs are low. In contrast, states will act as “draggers” (resisting stringent/proactive environmental foreign policy) when their combined ecological vulnerability is low and their abatement costs are high. States caught between “pushers” and “draggers” in terms of the environmental cost-benefit ratio find themselves as “intermediates” in environmental foreign policy-making given that they have ecological incentives to foster stringent/proactive policies but simultaneously have disincentives to act accordingly. Depending on the actual ratio between costs and benefits, intermediate countries can sway either towards proaction or resistance. The last classificatory box contains states (“bystanders”) that have neither the ecological incentive to push for stringent/proactive policies nor the sufficient economic disincentive to oppose such stringent policies. These states are likely, nonetheless, to take a more ambitious policy stance than “dragger” states.

Figure 2.044

Elaborating on this logic, Rowlands (1995) suggests that when choosing which foreign policy to pursue a state will balance the costs of changing the status quo (taking action) with the costs of inaction. In turn, the costs of action depend on 1) the costs of changing the activity that is causing the environmental damage and 2) the benefits derived from avoiding environmental damage that would otherwise have occurred. The costs of inaction depend on 1) the costs associated with environmental damage and 2) the benefits from continuing the damaging activities. As this proposition is extremely difficult to quantify in the real world due to limited data availability it would be analytically advantageous to express the same reasoning using a simpler proposition. Thus, I will assume that in circumstances where the benefits of action (i.e. the costs of inaction) outweigh the costs of action (i.e. the benefits of inaction) a state will be inclined to pursue a more proactive stance on the environment. This simple proposition expresses the essence of the theoretical model above45.

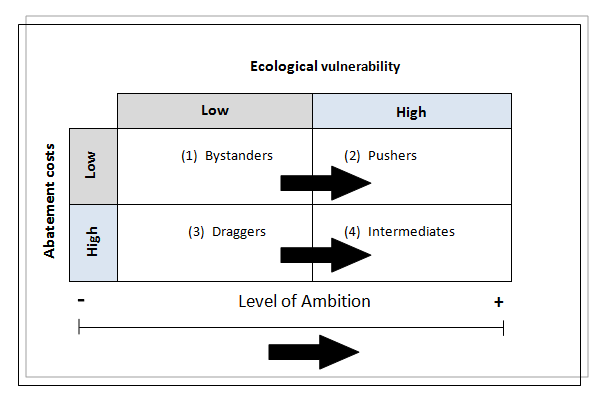

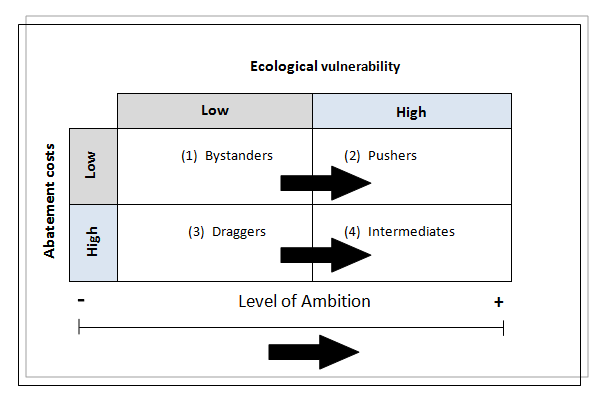

Incorporating the logic of the simplified proposition above into Sprinz & Vaahtoranta’s (1994) original model (see Figure 2.0) would entail introducing a ‘dynamic’ factor to an otherwise static model46. In order to enable the model to predict changes in the environmental foreign policies of countries the original model needs to be slightly modified (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.147

Assuming that the abatement costs of countries will be relatively fixed48 in the short to medium term the interest-based model would posit that any changes in a given country’s climate policy must be accredited to changes in the level of climate vulnerability. Following from this, keeping abatement costs constant in the short term a more ambitious climate policy will only be pursued if climate vulnerability increases. This proposition, in turn, can be utilised for analytical purposes.

To summarise, the best way to think about model A is by borrowing terminology from economics and applying it to a political setting. A country is basically assumed to find itself in a foreign policy equilibrium characterised by its national interests (as a function of ecological vulnerability and abatement costs) being perfectly aligned with its environmental foreign policy. Changes to the equilibrium due to changes in the country’s national interest will give rise to an alteration of the country’s existing environmental foreign policy. When the country’s environmental foreign policy is aligned with its national interests the country will find itself yet again in a state of equilibrium.

2.1.2 LIMITATIONS OF THE UNITARY ACTOR MODEL

Model A remains unrivalled in terms of the parsimony and clarity that it offers to the analyst of environmental foreign policy. However, with any model relying on a stringent set of economistic assumptions certain limitations need to be explicated. To be sure, the same theoretical elements that make the unitary actor model a powerful analytical tool simultaneously represent its main analytical weakness. Critics of the application of economistic assumptions to the field of politics would assert that vital nuances and complexities are inevitably omitted or simply overlooked due to the restrictive assumptions underpinning the unitary actor model. In other words, countries do not always exhibit behavioural characteristics similar to that of the rational, unitary and utility-maximising economic agent but will at least some of the time act in ways opposed to these assumptions (Rowlands, 1995). In order to accommodate such criticism the present dissertation, by way of its analytical strategy of complementarity, will supplement the unitary actor model with another theoretical framework more capable of capturing political complexities. The domestic politics model49, given its set of less stringent assumptions, enables this framework to capture vital insights in the form of intra-state dynamics omitted by the unitary actor model, thus contributing to a significantly more nuanced analysis.

2.2 MODEL B: DOMESTIC POLITICS MODEL

Where Model A conceives of the state as a ‘black box’ with a given set of objective national interests which can be deduced from factors lying outside of the state, the Domestic Politics Model asserts the need to look at intra-state dynamics in order to understand the policy position taken by a given state. In other words, the Domestic Politics Model raises two central questions: “(...) what are the interests of the state?, and what is the role of interests within the state?” (Barkdull & Harris, 2009:30). In this vein, the Domestic Politics Model argues that, within the state, a continuous game of intra-state bargaining is constantly being played out between different actors with differing agendas and interests. Analogous to Graham Allison’s (1969) bureaucratic politics model political outcomes are conceptualised as the result of “(...) compromise, coalition, competition, and confusion among government officials (...); the activity from which the outcomes emerge is best characterized as bargaining” (Allison, 1969:708). Underdal (1998) further develops this conceptualisation of political outcomes by asserting that “(...) decisions and policies [of the state] are formed through a series of policy games over which no single actor has full control (Underdal, 1998:12). Given that the policy position of a state is subject to intense intra-state bargaining this opens up for the possibility of sub-optimal outcomes50. However, sub-optimal outcomes are not the result of irrational behaviour; in fact, the assumed level of rationality is the same for both the Unitary Actor Model and the Domestic Politics Model. Instead sub-optimal outcomes are derived from the relaxation of the assumption of state unity by emphasising that “(...) sub-actors pursue multiple and to some extent conflicting objectives” (Ibid:12). The ensuing outcome is then assumed to be a weighed aggregate of the actors involved in the political bargaining process. Thus, where the state in the Unitary Actor Model is assumed to choose any set of policy options that will maximise the likelihood of attaining the objective national interest the Domestic Politics Model relinquishes this possibility as the national interest is perceived an aggregation of the organisational interests of multiple policy actors. Therefore, any objectively given national interest in conflict with intra-state interests will have a reduced likelihood of being pursued.

2.2.1 FRAGMENTED AUTHORITARIANISM

Both Allison’s (1969) and Underdal’s (1998) conceptualisations of the state as a political battlefield are mostly applied to Western style government. However, within the scope of the Domestic Politics Model one also finds sufficient room to incorporate a specific Chinese typology of state. This typology dubbed fragmented authoritarianism (FA) (Lieberthal & Oksenberg, 1988) has many overlaps with the conceptualisation suggested by Allison and Underdal. In fact, one could go as far as to argue that FA is merely the extension of the Domestics Politics Model proper with Chinese characteristics. Employing the typology of FA serves the present purposes well as FA remains the most durable heuristic tool through which to study Chinese politics (Mertha, 2009:996) and as such, the most accurate account of Chinese policy-making.

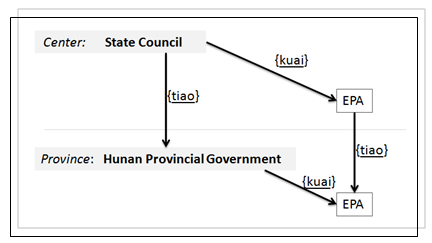

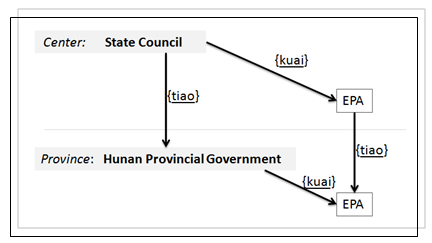

The idea of FA must be understood as presenting an alternative to the simplistic notion of China as a monolithic communist authoritarian state often found in mainstream literature on China51. FA asserts that the enormous size of China coupled with its particular bureaucratic structure of overlapping horizontal and vertical lines of authority (see Figure 2.2) has created a highly fragmented political system where intra-agency bargaining is rife at each step of the policy-making process and implementation is weak and stifled by the many conflicting interests/incentives of local government branches vis-a-vis the central government. The particular structure of authority found in China can be characterised as a cellular structure meaning that any Chinese bureaucratic/organisational entity between the macro-level (the central government) and the micro-level (the local level) will find itself constantly being exposed to directives from the side (kuai) and from above (tiao) creating an often elongated and protracted policy- and implementation process.

Figure 2.252

As a consequence of the fragmented nature of its policy-making and implementation process the current Chinese state has involuntarily created spaces for autonomy and bargaining loopholes, thus making it susceptible to influences not only from state representatives but also increasingly from influences outside of the state. The empirical ramifications of this is a far more pluralised policy-making process where political actors formally barred from partaking in the policy-making process have managed to take advantage of the fragmented system and gain access and influence on policy outcome. China scholar Andrew Mertha (2009:997) has pointed out that:

The analytical implication of this is that when analysing the shift in China’s climate policies it becomes crucial to look beyond formal channels of influence and include a new set of actors. Within environmental policy-making it has been emphasised that the policy entrepreneurs of most importance in a Chinese context are business interests (Oh, 2012).

Thus, when analysing China’s climate policy one should look for interest aggregation not only in relation to actors embedded within the official Chinese policy-making institutions/bureaucracies, but also at the interests of societal actors. It follows from the reasoning underpinning Model B that an increased level of ambition in China’s climate policies can only be achieved in a conducive policy environment. Given the propositions made by Model B, such a conducive environment would exist when the interests in favour of an increased level of climate ambition outweigh the interests against such ambitions i.e. when the net aggregation of interests of the primary policy actors is positive. This in turn depends on such intra-state factors, such as state structure which frames the context for interest aggregation, the power asymmetries between the relevant policy actors given the institutional hierarchy and the influence of actors beyond the confines of the state apparatus such as business interests. In other words, for the analysis to be fruitful it is necessary to peer deep into the ‘engine-room’ of the Chinese policy-making system in order to obtain information about the policy context in which China’s climate policies are hatched. It is important to remember that the existence of a non-conducive policy environment does not preclude the possibility of an ambitious Chinese climate policy, however, a non-conducive policy environment could act as a constraint to achieving a policy more ambitious than the status quo i.e. result in a sub-optimal outcome vis-a-vis China’s objective interests (see Model A).

Recapping, where Model A perceived of the state as a unitary actor endowed with objective interests Model B relaxes this stringent assumption and opens the ‘black box’ of the state acknowledging that domestic politics is a significant driver of policy. In fact, most political scientists would probably agree that a parsimonious model such as Model A where internal dynamics are bracketed for the sake of simplicity is useful as a first analytical step because it helps define what a given state ought to strive for in terms of its objective national interests but also that such a model cannot stand alone. Recognising that real-world phenomena are often complex and the result of conflict and bargaining between political actors Model B incorporates an understanding of the nitty-gritty of such real-world politics by asserting that bureaucratic actors and actors outside of the formal policy-making process have become sources of policy in their own right. Therefore, by employing Model B a more nuanced understanding of the drivers behind China’s climate policy can be achieved and more importantly, this model can explain potential policy deviations from China’s objective national interests, as elucidated by Model A.

2.2.2 LIMITATIONS OF THE DOMESTIC POLITICS MODEL

As was the case with the Unitary Actor Model, the Domestic Politics Model comes with its own set of limitations given the assumptions underpinning this framework. Most significantly, the assumption of rationality can be contested on the grounds that the rationality of sub-national policy actors ought not generate sub-optimal policy outcomes. The assertion of rationality in this model runs the risk of undermining the tenets of what actually constitutes rationality in the first place. If the functionality of rationality as an analytical concept is to be maintained irrespective of context, then adapting rationality to fit the situational context can seem detrimental to achieving some sort of standard definition of rationality. Some critics may argue that actors at the sub-national level are not acting in accordance with rationality if the objective national interest is subordinated to intra-state interest bargaining. Despite this explanatory weakness the controversy over what constitutes rationality and the explanatory ramifications thereof is beyond the scope of this paper and will not be pursued further in this dissertation.

Another significant case in point regarding the limitations of the Domestic Politics Model is the somewhat arbitrary assumption that policy outcomes can be perceived as a weighted aggregate of intra-state interests. The assertion that policy outcomes are often the result of interest bargaining between multiple types of interests seems valid, however, it is less obvious exactly how these multiple types of interests are distinguished and what their individual importance is. As Allison (1969:707) points out the weighted interest aggregate is the conflation of “(...) national, organizational, and personal goals (...)”, which effectively implies that three types of interests need segregating. Allison (1969) himself, however, does not provide any turn-key solution to this problem of operationalisation.

2.3 THE (DELIBERATE) OMISSION OF CLASSIC GAME-THEORY

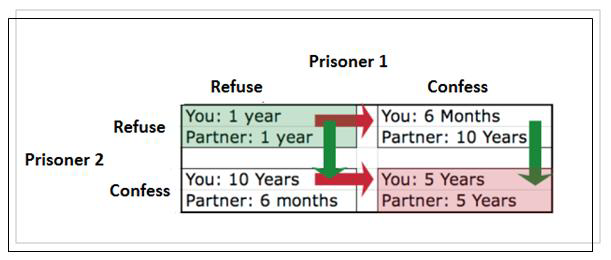

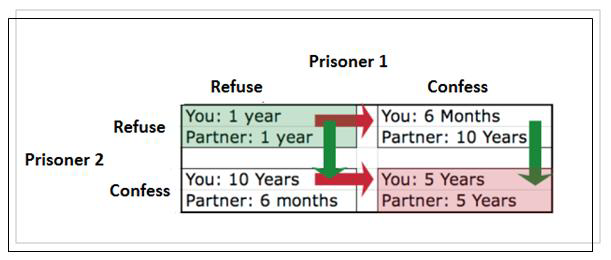

The behavioural assumptions on which the two previous theoretical models are predicated53 could also warrant the inclusion of a third theoretical framework also widely applied to climate politics54. Classic game-theory55 conceptualises the interaction among actors as taking place in strategic games where the outcome depends on the pay-off structure facing game participants. These games, in turn, can then be varied in endless ways according to the number of games and number of players. However, in its simplest form, game-theory posits that rational actors will systematically opt for sub-optimal outcomes. The metaphor of “the prisoners’ dilemma” (PD) best captures the essence of such strategic policy games. In this scenario, the participants (prisoner 1 and 2) face a pay-off structure identical to Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.356

Confronted by this pay-off structure the two prisoners57 will rationally decide to confess irrespective of the actions of the other prisoner as this decision is the superior strategy faced with the uncertainty of the actions of the other prisoner. Therefore, both prisoners decide to confess and serve five years in prison despite the fact that cooperating (i.e. both refusing) would significantly lower the prison sentences for both prisoners.

Given the public good58 properties of climate protection59, global climate change politics shares characteristics similar to the PD. Countries will have incentives to free-ride or defect as this is the optimal strategy faced with the uncertainty of not knowing the actions of other countries. Therefore, like in the PD, climate policy negotiators will opt for the sub-optimal outcome of non-cooperation60 as this is the most rational strategy. Put in simpler terms, negotiators know that the long-term effect of climate change is likely to be devastating to all countries. However, they also know that acting unilaterally is not enough to secure sufficient climate protection. Obviously, cooperating on the provision of climate protection (by sharing the costs) is the most optimal outcome but given the uncertainty regarding the reciprocity of other participants, countries are discouraged from cooperating since unilaterally shouldering the costs is an untenable position.

Despite the argument that global climate politics resembles the PD I will not include this theoretical model in the present dissertation for the following two reasons:

1) There are already a plethora of studies applying classic game-theory to climate politics but, conversely, only very few that, like the present dissertation, seek to fuse the insights provided by the unitary actor model with the insights of the domestic politics model. As a consequence of this underrepresentation I find it more engaging to pursue a somewhat untraditional theoretical path61.

2) Furthermore, analyses employing game-theory have a tendency to treat players as equals (Snidal, 1985). However, I would argue that countries seldomly negotiate as equal partners given that some players have more at stake in the resultant policy outcome than others vis-a-vis their respective interests. This is particularly true for climate change politics where the impact of global climate change is likely to be diverse62, thus strategically disadvantaging some countries whilst simultaneously advantaging others and as a consequence ‘rigging’ the game in advance. Therefore, these special circumstances make game-theory less suited as an explanatory framework of climate politics.

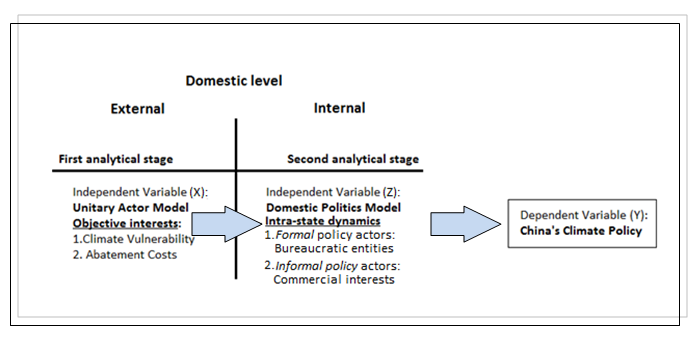

2.4 EXPLANATORY MODEL – COMBINING THE TWO THEORETICAL MODELS

As has been elucidated above, both the unitary actor model and the domestic politics model are strands of interest-based theory which places analytical emphasis on the influence of interests in the formulation of a country’s climate policy. Seeing that climate change has the potential to adversely affect Chinese interests these two models in conjunction make for a suitable theoretical framework for the analysis of China’s climate policy. Despite their individual differences the two models share a common commitment to the proposition that interests63 represent the key explanatory variables when analysing climate policies. This shared commitment to interests makes the two theoretical models compatible, which helps facilitate the theoretical strategy pursued here of complementarity rather than competition. However, a contingency exists regarding the timing and sequencing of the employed models. In other words, which model should be employed first and which should come second? In the present dissertation, the analytical logic followed here posits that Model A should precede Model B given the temporal consideration that most countries will formulate policies as a response to its objective national interests. Put differently, most countries will act reactively to the changing conditions of their external environment rather than pre-emptively anticipating future developments. For these reasons, I propose the following analytical model (see Figure 2.4) which will structure the analysis of the present dissertation:

Figure 2.4

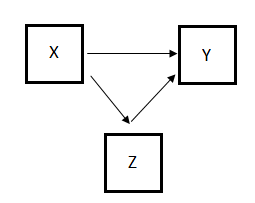

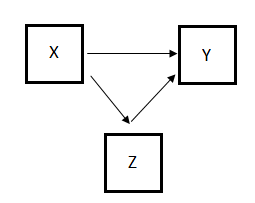

Underlying this analytical model are the causal relationships suggested by the two theoretical models (Model A and B) elucidated in the sections above. The causation can be characterised as probabilistic incorporating both a direct causal relationship (between X and Y) as well as an indirect causal relationship (between X and Z; Z and Y) (see Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5

The unitary actor model posits that China’s climate policy will be affected by its aggregated national interest (X) in terms of climate change, which, in turn, depends on China’s level of climate vulnerability (X1) and abatement costs (X2). If the costs associated with China’s climate vulnerability outweigh China’s abatement costs then the aggregated national interest will cause an increased level of climate policy proaction and vice versa. However, although the aggregated national interest serves as a powerful motivation for changing policies this causal relationship (between X and Y) cannot stand on its own but needs to be complemented by considerations over internal political dynamics (Sprinz & Vaahtoranta, 1994, 2002; Rowlands, 1995). More than likely countries will not exhibit the level of political cohesion suggested by the unitary actor model. Instead, political factions embedded within the domestic political system tend to be less informed by the aggregated national interest and more driven by narrow sets of organisational interests. Thus, intra-state interest-bargaining affect the outcome of the resultant policy response to the national interest and serves as a mediating causal relationship between X, Z and Y. The outcome of interest bargaining (Z) depends on both the interests (Z1) and the political power (Z2) of the actors involved. The domestic politics model posits that when the interests of the most powerful political actors are aligned with the aggregated national interest then the likelihood of formulating policies aligned with the national interest increases. Conversely, if the interests of the most powerful political actors are opposed to the national interest then the likelihood of a policy response aligned with the national interest decreases.

This article is a part of a master's thesis from 2013.

| < Introduction | Table of Contents | Methodology > |

2.0 THEORY

As mentioned above, focusing on the significance of interests is a useful starting point for the analysis of climate politics. Global climate change is at its most basic ultimately about interests since changing climatic conditions have the potential to (re-)distribute benefits and assign costs to different actors, thus affecting their preferences. In the context of China, an assertion of the significance of interests is particularly valid since climate change is intimately linked with the prospects of securing continued economic growth which, in turn, has ramifications for political stability. The (re-)distributive process caused by climate change takes place both between and within countries. In the introduction I argued that in the case of China, dynamics at the domestic level take primacy in the formulation of China’s climate policy due to, among other things, a strict adherence to the principle of sovereignty. As a result of this, the Chinese process of redistribution will primarily be couched in domestic terms which warrant an analytical focus on domestic factors. The conjunction of domestic factors shaping China’s climate policy will be analysed employing two complementary yet distinct theoretical models. Both models, however, emphasise the importance of interests in the formation of climate policy but operate at different analytical levels. By combining the respective insights of both models facilitates a more comprehensive explanation of the recent shift in China’s climate policy.

2.1 INTEREST-BASED THEORY37

The group of interest-based theories shares a similar starting point in terms of the assertion that interests38 matter for outcomes of foreign policy. Just as the famous assertion made by neoliberal institutionalists39 that “institutions matter” in international politics so does the group of interest-based theory stress that (national) interests matter when governments decide on which foreign policy to adopt.

Underlying interest-based theories is a shared set of core assumptions40 emphasising that interests matter because these inform and carry with them behavioural implications. It is assumed that actors have the ability to hold several and competing interests and rank these in accordance with their respective contribution to utility-maximisation. This assumption has behavioural implications as interest-based theory assert that when faced with a decision, an actor will choose the action or set of actions most aligned with its ranked interests. Central to this are the respective costs and benefits of different sets of actions. Given that the actor is rational and utility maximising interest-based theory would predict that faced with a choice an actor will choose the action with most benefits and least costs. Rationality also entails that actors are assumed to be susceptible and responsive to new information about future costs and benefits in order to avoid short term gains at the expense of larger future gains.

Depending on both the nature of the political issue in question, as well as characteristics pertaining to the actor (individual, firm, country etc.) involved, the set of core assumptions can be either tightened or relaxed in order to fit the context in question. In the case of climate change policy, interest-based theory is most often employed at the aggregate level, treating the state is a unitary actor faced with a set of national cost and benefits from which net benefits can be derived (Dietz et. al., 2012). However, in reality, countries seldomly function as fully unitary or fully rational entities, but are influenced by factors embedded within the domestic political context. Different competing pressure groups will seek to influence the policy-making process in order to achieve their set of exclusive interests. Furthermore, government agencies will compete in order to enhance their organisational budgets and increase their prominence through expanding the portfolio of responsibilities, thus influencing the policy-making process. For these reasons, the present dissertation includes two interest-based explanatory models. Where the first model (Model A) conceives China’s climate policy as the result solely of China’s aggregated national interest, the second model (Model B), building on Model A, includes the influence of domestic factors relevant to the political landscape in China.

2.1.1 MODEL A: THE UNITARY ACTOR MODEL

The unitary actor model41 is an interest-based explanatory approach to foreign policy decision-making where actions of foreign policy are conceptualised as the result of the unitary state acting strategically towards the attainment of its national objectives or as a response to an external threat. The model starts with the basic assumption of the state as a self-interested unitary actor endowed with the ability to act rationally. It is assumed that the behaviour of the state actor is chiefly motivated by a desire to achieve its national interests which are assumed to be objectively given. The unitary state actor will strive to achieve its national interest as these will increase the likelihood of state survival. Given the rationality of the state it is further assumed that the state has the ability to make rational choices vis-a-vis its national interests. In other words, the unitary state will choose the foreign policy option which has the lowest costs and maximum gains depending on such conditioning factors as the values assigned to different national policy objectives; alternative courses of action and the various sets of consequences (Allison, 1969). It is further assumed that the state has or can obtain perfect information regarding its national interest. No matter how complex reality is, the unitary actor model posits that accurate cost-benefit analyses are always possible to conduct from the perspective of the unitary state actor.

Applied to the case of China, the unitary actor model in its purest form, as elucidated above, would start out by defining China’s overall national interests as these dictate options across policy areas. In the case of China, taking primacy are concerns over the continued survival and integrity of the Chinese political regime which, in turn, rest squarely on maintaining sovereignty and economic development. From this view, climate policy does not factor into the equation since climate policy falls outside the immediate scope of what constitutes national interests despite indirectly impacting on the likelihood of attaining national interests.

For this reason, the unitary actor model proper needs to be slightly augmented in order to encompass climate policy dynamics. This modified version of Model A questions the assumption that climate change lies outside of national interest. Instead, it assumes that climate change fundamentally alters the cost-benefit ratios of the unitary state actor.

2.1.1.1THE INTEREST-BASED EXPLANATION OF INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY

The slightly modified version of the unitary actor model, dubbed the “Interest-Based Explanation of International Environmental Policy” (Sprinz & Vaahtoranta, 1994), makes parallel assumptions to the unitary actor model. However, setting it apart is an assumption that what constitutes national interests will differ according to the situational context. Overarching national interests such as sovereignty and survival are obviously assumed to be important but depending on the situational context the nature of what constitutes national interests will vary. Sprinz & Vaahtoranta (1994) argue that the environmental politics of different countries mirrors their immediate national interests within the context of the environment. The overarching national interests will then serve as guidelines to what can feasibly be perceived as a given country’s interests i.e. the immediate interests within a given situational context are assumed to be aligned with the country’s overall national interests. Following from this, within the context of environmental foreign policy, what matters is a country’s level of ecological vulnerability42 and abatement costs43. The model suggests that countries will 1) seek to “(...) avoid vulnerability (...)” (Ibid:78) and that 2) “States are more inclined to participate in environmental protection when the costs of compliance are relatively minor” (Ibid:78ff). Based on these behavioural assumptions, the interest-based model suggests that countries will act as either “pushers”, “draggers”, “bystanders”, or “intermediates” (see Figure 2.0) depending on the cost-benefit ratios related to their respective levels of vulnerability and abatement costs. States will act as “pushers” (seeking stringent/proactive environmental foreign policy) when their combined ecological vulnerability is high and abatement costs are low. In contrast, states will act as “draggers” (resisting stringent/proactive environmental foreign policy) when their combined ecological vulnerability is low and their abatement costs are high. States caught between “pushers” and “draggers” in terms of the environmental cost-benefit ratio find themselves as “intermediates” in environmental foreign policy-making given that they have ecological incentives to foster stringent/proactive policies but simultaneously have disincentives to act accordingly. Depending on the actual ratio between costs and benefits, intermediate countries can sway either towards proaction or resistance. The last classificatory box contains states (“bystanders”) that have neither the ecological incentive to push for stringent/proactive policies nor the sufficient economic disincentive to oppose such stringent policies. These states are likely, nonetheless, to take a more ambitious policy stance than “dragger” states.

Figure 2.044

Elaborating on this logic, Rowlands (1995) suggests that when choosing which foreign policy to pursue a state will balance the costs of changing the status quo (taking action) with the costs of inaction. In turn, the costs of action depend on 1) the costs of changing the activity that is causing the environmental damage and 2) the benefits derived from avoiding environmental damage that would otherwise have occurred. The costs of inaction depend on 1) the costs associated with environmental damage and 2) the benefits from continuing the damaging activities. As this proposition is extremely difficult to quantify in the real world due to limited data availability it would be analytically advantageous to express the same reasoning using a simpler proposition. Thus, I will assume that in circumstances where the benefits of action (i.e. the costs of inaction) outweigh the costs of action (i.e. the benefits of inaction) a state will be inclined to pursue a more proactive stance on the environment. This simple proposition expresses the essence of the theoretical model above45.

Incorporating the logic of the simplified proposition above into Sprinz & Vaahtoranta’s (1994) original model (see Figure 2.0) would entail introducing a ‘dynamic’ factor to an otherwise static model46. In order to enable the model to predict changes in the environmental foreign policies of countries the original model needs to be slightly modified (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.147

Assuming that the abatement costs of countries will be relatively fixed48 in the short to medium term the interest-based model would posit that any changes in a given country’s climate policy must be accredited to changes in the level of climate vulnerability. Following from this, keeping abatement costs constant in the short term a more ambitious climate policy will only be pursued if climate vulnerability increases. This proposition, in turn, can be utilised for analytical purposes.

To summarise, the best way to think about model A is by borrowing terminology from economics and applying it to a political setting. A country is basically assumed to find itself in a foreign policy equilibrium characterised by its national interests (as a function of ecological vulnerability and abatement costs) being perfectly aligned with its environmental foreign policy. Changes to the equilibrium due to changes in the country’s national interest will give rise to an alteration of the country’s existing environmental foreign policy. When the country’s environmental foreign policy is aligned with its national interests the country will find itself yet again in a state of equilibrium.

2.1.2 LIMITATIONS OF THE UNITARY ACTOR MODEL

Model A remains unrivalled in terms of the parsimony and clarity that it offers to the analyst of environmental foreign policy. However, with any model relying on a stringent set of economistic assumptions certain limitations need to be explicated. To be sure, the same theoretical elements that make the unitary actor model a powerful analytical tool simultaneously represent its main analytical weakness. Critics of the application of economistic assumptions to the field of politics would assert that vital nuances and complexities are inevitably omitted or simply overlooked due to the restrictive assumptions underpinning the unitary actor model. In other words, countries do not always exhibit behavioural characteristics similar to that of the rational, unitary and utility-maximising economic agent but will at least some of the time act in ways opposed to these assumptions (Rowlands, 1995). In order to accommodate such criticism the present dissertation, by way of its analytical strategy of complementarity, will supplement the unitary actor model with another theoretical framework more capable of capturing political complexities. The domestic politics model49, given its set of less stringent assumptions, enables this framework to capture vital insights in the form of intra-state dynamics omitted by the unitary actor model, thus contributing to a significantly more nuanced analysis.

2.2 MODEL B: DOMESTIC POLITICS MODEL

Where Model A conceives of the state as a ‘black box’ with a given set of objective national interests which can be deduced from factors lying outside of the state, the Domestic Politics Model asserts the need to look at intra-state dynamics in order to understand the policy position taken by a given state. In other words, the Domestic Politics Model raises two central questions: “(...) what are the interests of the state?, and what is the role of interests within the state?” (Barkdull & Harris, 2009:30). In this vein, the Domestic Politics Model argues that, within the state, a continuous game of intra-state bargaining is constantly being played out between different actors with differing agendas and interests. Analogous to Graham Allison’s (1969) bureaucratic politics model political outcomes are conceptualised as the result of “(...) compromise, coalition, competition, and confusion among government officials (...); the activity from which the outcomes emerge is best characterized as bargaining” (Allison, 1969:708). Underdal (1998) further develops this conceptualisation of political outcomes by asserting that “(...) decisions and policies [of the state] are formed through a series of policy games over which no single actor has full control (Underdal, 1998:12). Given that the policy position of a state is subject to intense intra-state bargaining this opens up for the possibility of sub-optimal outcomes50. However, sub-optimal outcomes are not the result of irrational behaviour; in fact, the assumed level of rationality is the same for both the Unitary Actor Model and the Domestic Politics Model. Instead sub-optimal outcomes are derived from the relaxation of the assumption of state unity by emphasising that “(...) sub-actors pursue multiple and to some extent conflicting objectives” (Ibid:12). The ensuing outcome is then assumed to be a weighed aggregate of the actors involved in the political bargaining process. Thus, where the state in the Unitary Actor Model is assumed to choose any set of policy options that will maximise the likelihood of attaining the objective national interest the Domestic Politics Model relinquishes this possibility as the national interest is perceived an aggregation of the organisational interests of multiple policy actors. Therefore, any objectively given national interest in conflict with intra-state interests will have a reduced likelihood of being pursued.

2.2.1 FRAGMENTED AUTHORITARIANISM

Both Allison’s (1969) and Underdal’s (1998) conceptualisations of the state as a political battlefield are mostly applied to Western style government. However, within the scope of the Domestic Politics Model one also finds sufficient room to incorporate a specific Chinese typology of state. This typology dubbed fragmented authoritarianism (FA) (Lieberthal & Oksenberg, 1988) has many overlaps with the conceptualisation suggested by Allison and Underdal. In fact, one could go as far as to argue that FA is merely the extension of the Domestics Politics Model proper with Chinese characteristics. Employing the typology of FA serves the present purposes well as FA remains the most durable heuristic tool through which to study Chinese politics (Mertha, 2009:996) and as such, the most accurate account of Chinese policy-making.

The idea of FA must be understood as presenting an alternative to the simplistic notion of China as a monolithic communist authoritarian state often found in mainstream literature on China51. FA asserts that the enormous size of China coupled with its particular bureaucratic structure of overlapping horizontal and vertical lines of authority (see Figure 2.2) has created a highly fragmented political system where intra-agency bargaining is rife at each step of the policy-making process and implementation is weak and stifled by the many conflicting interests/incentives of local government branches vis-a-vis the central government. The particular structure of authority found in China can be characterised as a cellular structure meaning that any Chinese bureaucratic/organisational entity between the macro-level (the central government) and the micro-level (the local level) will find itself constantly being exposed to directives from the side (kuai) and from above (tiao) creating an often elongated and protracted policy- and implementation process.

Figure 2.252

As a consequence of the fragmented nature of its policy-making and implementation process the current Chinese state has involuntarily created spaces for autonomy and bargaining loopholes, thus making it susceptible to influences not only from state representatives but also increasingly from influences outside of the state. The empirical ramifications of this is a far more pluralised policy-making process where political actors formally barred from partaking in the policy-making process have managed to take advantage of the fragmented system and gain access and influence on policy outcome. China scholar Andrew Mertha (2009:997) has pointed out that:

(...) the political dynamics captured in the FA framework provide policy entrepreneurs with a road map, a playbook by which they can pursue their policy goals. They adopt the strategies that traditional institutions have used for decades to pursue their agendas and institutional mandates.

The analytical implication of this is that when analysing the shift in China’s climate policies it becomes crucial to look beyond formal channels of influence and include a new set of actors. Within environmental policy-making it has been emphasised that the policy entrepreneurs of most importance in a Chinese context are business interests (Oh, 2012).

Thus, when analysing China’s climate policy one should look for interest aggregation not only in relation to actors embedded within the official Chinese policy-making institutions/bureaucracies, but also at the interests of societal actors. It follows from the reasoning underpinning Model B that an increased level of ambition in China’s climate policies can only be achieved in a conducive policy environment. Given the propositions made by Model B, such a conducive environment would exist when the interests in favour of an increased level of climate ambition outweigh the interests against such ambitions i.e. when the net aggregation of interests of the primary policy actors is positive. This in turn depends on such intra-state factors, such as state structure which frames the context for interest aggregation, the power asymmetries between the relevant policy actors given the institutional hierarchy and the influence of actors beyond the confines of the state apparatus such as business interests. In other words, for the analysis to be fruitful it is necessary to peer deep into the ‘engine-room’ of the Chinese policy-making system in order to obtain information about the policy context in which China’s climate policies are hatched. It is important to remember that the existence of a non-conducive policy environment does not preclude the possibility of an ambitious Chinese climate policy, however, a non-conducive policy environment could act as a constraint to achieving a policy more ambitious than the status quo i.e. result in a sub-optimal outcome vis-a-vis China’s objective interests (see Model A).

Recapping, where Model A perceived of the state as a unitary actor endowed with objective interests Model B relaxes this stringent assumption and opens the ‘black box’ of the state acknowledging that domestic politics is a significant driver of policy. In fact, most political scientists would probably agree that a parsimonious model such as Model A where internal dynamics are bracketed for the sake of simplicity is useful as a first analytical step because it helps define what a given state ought to strive for in terms of its objective national interests but also that such a model cannot stand alone. Recognising that real-world phenomena are often complex and the result of conflict and bargaining between political actors Model B incorporates an understanding of the nitty-gritty of such real-world politics by asserting that bureaucratic actors and actors outside of the formal policy-making process have become sources of policy in their own right. Therefore, by employing Model B a more nuanced understanding of the drivers behind China’s climate policy can be achieved and more importantly, this model can explain potential policy deviations from China’s objective national interests, as elucidated by Model A.

2.2.2 LIMITATIONS OF THE DOMESTIC POLITICS MODEL

As was the case with the Unitary Actor Model, the Domestic Politics Model comes with its own set of limitations given the assumptions underpinning this framework. Most significantly, the assumption of rationality can be contested on the grounds that the rationality of sub-national policy actors ought not generate sub-optimal policy outcomes. The assertion of rationality in this model runs the risk of undermining the tenets of what actually constitutes rationality in the first place. If the functionality of rationality as an analytical concept is to be maintained irrespective of context, then adapting rationality to fit the situational context can seem detrimental to achieving some sort of standard definition of rationality. Some critics may argue that actors at the sub-national level are not acting in accordance with rationality if the objective national interest is subordinated to intra-state interest bargaining. Despite this explanatory weakness the controversy over what constitutes rationality and the explanatory ramifications thereof is beyond the scope of this paper and will not be pursued further in this dissertation.

Another significant case in point regarding the limitations of the Domestic Politics Model is the somewhat arbitrary assumption that policy outcomes can be perceived as a weighted aggregate of intra-state interests. The assertion that policy outcomes are often the result of interest bargaining between multiple types of interests seems valid, however, it is less obvious exactly how these multiple types of interests are distinguished and what their individual importance is. As Allison (1969:707) points out the weighted interest aggregate is the conflation of “(...) national, organizational, and personal goals (...)”, which effectively implies that three types of interests need segregating. Allison (1969) himself, however, does not provide any turn-key solution to this problem of operationalisation.

2.3 THE (DELIBERATE) OMISSION OF CLASSIC GAME-THEORY

The behavioural assumptions on which the two previous theoretical models are predicated53 could also warrant the inclusion of a third theoretical framework also widely applied to climate politics54. Classic game-theory55 conceptualises the interaction among actors as taking place in strategic games where the outcome depends on the pay-off structure facing game participants. These games, in turn, can then be varied in endless ways according to the number of games and number of players. However, in its simplest form, game-theory posits that rational actors will systematically opt for sub-optimal outcomes. The metaphor of “the prisoners’ dilemma” (PD) best captures the essence of such strategic policy games. In this scenario, the participants (prisoner 1 and 2) face a pay-off structure identical to Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.356

Confronted by this pay-off structure the two prisoners57 will rationally decide to confess irrespective of the actions of the other prisoner as this decision is the superior strategy faced with the uncertainty of the actions of the other prisoner. Therefore, both prisoners decide to confess and serve five years in prison despite the fact that cooperating (i.e. both refusing) would significantly lower the prison sentences for both prisoners.

Given the public good58 properties of climate protection59, global climate change politics shares characteristics similar to the PD. Countries will have incentives to free-ride or defect as this is the optimal strategy faced with the uncertainty of not knowing the actions of other countries. Therefore, like in the PD, climate policy negotiators will opt for the sub-optimal outcome of non-cooperation60 as this is the most rational strategy. Put in simpler terms, negotiators know that the long-term effect of climate change is likely to be devastating to all countries. However, they also know that acting unilaterally is not enough to secure sufficient climate protection. Obviously, cooperating on the provision of climate protection (by sharing the costs) is the most optimal outcome but given the uncertainty regarding the reciprocity of other participants, countries are discouraged from cooperating since unilaterally shouldering the costs is an untenable position.

Despite the argument that global climate politics resembles the PD I will not include this theoretical model in the present dissertation for the following two reasons:

1) There are already a plethora of studies applying classic game-theory to climate politics but, conversely, only very few that, like the present dissertation, seek to fuse the insights provided by the unitary actor model with the insights of the domestic politics model. As a consequence of this underrepresentation I find it more engaging to pursue a somewhat untraditional theoretical path61.

2) Furthermore, analyses employing game-theory have a tendency to treat players as equals (Snidal, 1985). However, I would argue that countries seldomly negotiate as equal partners given that some players have more at stake in the resultant policy outcome than others vis-a-vis their respective interests. This is particularly true for climate change politics where the impact of global climate change is likely to be diverse62, thus strategically disadvantaging some countries whilst simultaneously advantaging others and as a consequence ‘rigging’ the game in advance. Therefore, these special circumstances make game-theory less suited as an explanatory framework of climate politics.

2.4 EXPLANATORY MODEL – COMBINING THE TWO THEORETICAL MODELS

As has been elucidated above, both the unitary actor model and the domestic politics model are strands of interest-based theory which places analytical emphasis on the influence of interests in the formulation of a country’s climate policy. Seeing that climate change has the potential to adversely affect Chinese interests these two models in conjunction make for a suitable theoretical framework for the analysis of China’s climate policy. Despite their individual differences the two models share a common commitment to the proposition that interests63 represent the key explanatory variables when analysing climate policies. This shared commitment to interests makes the two theoretical models compatible, which helps facilitate the theoretical strategy pursued here of complementarity rather than competition. However, a contingency exists regarding the timing and sequencing of the employed models. In other words, which model should be employed first and which should come second? In the present dissertation, the analytical logic followed here posits that Model A should precede Model B given the temporal consideration that most countries will formulate policies as a response to its objective national interests. Put differently, most countries will act reactively to the changing conditions of their external environment rather than pre-emptively anticipating future developments. For these reasons, I propose the following analytical model (see Figure 2.4) which will structure the analysis of the present dissertation:

Figure 2.4

Underlying this analytical model are the causal relationships suggested by the two theoretical models (Model A and B) elucidated in the sections above. The causation can be characterised as probabilistic incorporating both a direct causal relationship (between X and Y) as well as an indirect causal relationship (between X and Z; Z and Y) (see Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5

The unitary actor model posits that China’s climate policy will be affected by its aggregated national interest (X) in terms of climate change, which, in turn, depends on China’s level of climate vulnerability (X1) and abatement costs (X2). If the costs associated with China’s climate vulnerability outweigh China’s abatement costs then the aggregated national interest will cause an increased level of climate policy proaction and vice versa. However, although the aggregated national interest serves as a powerful motivation for changing policies this causal relationship (between X and Y) cannot stand on its own but needs to be complemented by considerations over internal political dynamics (Sprinz & Vaahtoranta, 1994, 2002; Rowlands, 1995). More than likely countries will not exhibit the level of political cohesion suggested by the unitary actor model. Instead, political factions embedded within the domestic political system tend to be less informed by the aggregated national interest and more driven by narrow sets of organisational interests. Thus, intra-state interest-bargaining affect the outcome of the resultant policy response to the national interest and serves as a mediating causal relationship between X, Z and Y. The outcome of interest bargaining (Z) depends on both the interests (Z1) and the political power (Z2) of the actors involved. The domestic politics model posits that when the interests of the most powerful political actors are aligned with the aggregated national interest then the likelihood of formulating policies aligned with the national interest increases. Conversely, if the interests of the most powerful political actors are opposed to the national interest then the likelihood of a policy response aligned with the national interest decreases.

| < Introduction | Table of Contents | Methodology > |

Posted by branner

on 24. May 2014, 17:06 0 comment(s) · 4374 views

Comments

No comments yet.

Join the debate on Theory:

Related content

| Threads | Replies | Last post |

| I have a theory | 123 | 16-06-2023 19:16 |

| Evolutionary Biology and the Endosymbiotic Theory of Consciousness. | 111 | 08-06-2023 02:39 |

| What is the cause of climate change based on the greenhouse gas theory? | 82 | 04-02-2023 20:51 |

| There is no scientific theory or evidence that suggest CO2 traps heat better than O2 or N2 | 533 | 30-01-2023 07:22 |

| Relativity theory | 317 | 03-11-2022 19:38 |